- https://goblinpunch.blogspot.com/2020/04/dungeoncrawling-languages.html

- https://monstersandmanuals.blogspot.com/2016/03/on-language.html

- https://monstersandmanuals.blogspot.com/2008/11/languages-or-why-we-shouldnt-be-able-to.html

- https://falsemachine.blogspot.com/2020/05/soft-ass-d.html (he covers language as a specific part of the post and I think his take is neat)

- https://thelastdaydawned.blogspot.com/2016/11/making-languages-make-sense.html

- http://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/38698/roleplaying-games/untested-fantasy-lorem-ipsum

- https://www.paperspencils.com/making-languages-relevant/

As a general rule of thumb, the more closely related two creatures are, the more likely they are able to be able to understand each other. Use the creature’s taxonomy to make a ruling. Magical or highly intelligent creatures may break these rules. • Same species (mouse): Can easily communicate. • Same family (rodent): Can speak and communicate, with some difficulty and difference of custom. • Same class (mammal): Make a WIL save to see if communication is possible. • Otherwise: Can’t directly communicate.

Knaves begin fluent in one native language and any languages they may derive from their background (e.g. Latin for the clergy, a foreign tongue for mercenaries and smugglers, etc.), and could even be literate if their background supports it. They gain bonus language fluencies/literacies = to half their Intelligence (rounded up). Points are spent to either gain verbal fluency or to gain literacy, one at a time.

Characters who can speak related languages can communicate but have a -2 on disposition and cannot be affected by verbal Charisma checks. Reading a related text will leave gaps or multiple interpretations. The referee should make a list of languages used in their setting and their relations.

It could probably be cleaned up but I needed to squeeze it into the page. Keep in mind that a starting character's Intelligence can be up to 6, but will likely be 1 or 2. As they level up, they can eventually get it as high as 10. That means that there's a language-learning mechanic already built into the leveling system, which is nice. But I also think I'd let a player learn more languages as a downtime activity if they requested it, since I want to reward that.

The main thing I want to explain is the idea of "related" languages. This pays lip service to some degree of realism in linguistics that most RPGs neglect, but the real reason I chose it is because I think it can add that extra layer of mechanical depth we need. It opens up the language barrier a little bit by allowing players to still have access to speech/text that they don't properly know. So having someone in the party who knows Italian means you can still interact with the Spanish merchants and the Romanian nomads you meet, even if it's a bit tenuous. Is this a stretch? Yes. But I like it.

I also tried to think about how, mechanically, you can represent the idea of "knowing" a language in such a peripheral way. Well, when it comes to verbal speech, I realized that I already have two layers of mechanics that splits the difference between player-skill and character-skill philosophies: I make my players actually talk and explain what they say, but I also let them make a CHA check in certain conditions.

Social gameplay in D&D is weird, you know? A lot of people just simplify it to real-life talking and have nothing more. Other people totally abstract it into gameplay mechanics and systemize the conversation into a minigame. I traffic in the middle, which some people find bizarre or impossible. When do you shift from natural talking to making a Charisma check? Usually it's when you've gotten past the introductions, then the superficialities and formalities, then the questions and clarifications to get on the same page of understanding, and you finally reach a tipping point where one party 1) defines a concrete stance, and 2) throws the ball in the other party's court. That is to say, Charisma checks are used when the social interaction reaches an "exchange" or a "confrontation." I never use them for regular stuff like buying items, asking for directions, shooting the shit, or whatever. It's there to resolve a disconnect between people of opposing positions.

That doesn't just mean persuasion and debate. It can be haggling or pleading. It can be flirting (often a cat-and-mouse game of convincing and counter-convincing), entertaining, intimidating, strategizing, and so on. Once a conversation turns towards one of those, eventually someone is going to propose a claim, offer, rationale, or incentive that the other person then responds to. It's kind of a weird, mechanical way of viewing human interaction, but it's a very real thing. In fact, learning to start reading social interactions with this lens is the key to social engineering, a skill that's very relevant to the adventuring lifestyle. One of the best selling books of all time is How to Make Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie, which covers this topic as well.

So my language rules focus on that exact tipping point. Know the language fluently? You can do any level of speech activity. Only know a related language? Well, you can still exchange information, but you cannot use the language well enough to ever make someone budge on something that they have a firm stance on. Their first impression of you will likely remain their only impression of you. If you wanted to, you could also apply the related penalties on someone who is learning a language but isn't yet fully fluent, to show that they're going through the transitionary stage.

Oh, and disposition gets thrown in here too because Reaction Rolls are a convenient mechanic to manipulate. In a perfect world, speaking a different language shouldn't affect this, because we should all be open-minded and helpful towards our fellow human. But Medieval societies were generally xenophobic, and that's built into the fabric of the world even in mechanical terms. Keep in mind that having no common languages reduces disposition by 4, so a -2 is actually an improvement.

When it comes to written text, this one is a bit more fiddly. I worry that, because I didn't give a precise mechanic, that makes it harder to use. It trusts that the referee will look at the text in its own context and be able to make a ruling on how the player could get "multiple interpretations" or have "gaps" in the meaning. Hopefully, it's not only a reasonable ruling to expect of the referee, but maybe even a fun one for them to make on the spot.

So How Do You Make a List of Languages?

Well, while I want the referee to have the freedom of designing the list themselves, I have some pointers on what makes a good list. For one thing, this system forces you to start designing your list with built-in connections between related languages. That's really cool and players like it.

But I also try not to just have languages defined by cultures/species. Obviously, humans and elves and dwarves all need their own languages. But all that really changes is "which towns can the party go to?" I think that having languages defined by social role is also interesting. So while all listed languages are "vernacular/vulgar" by default, most of them will have an upper-class "High" variant (e.g. High Valyrian or the Queen's English or Modern Standard Arabic) often used for scholarly texts and talking to nobility, and most will have an antiquated "Old" variant (e.g. Old Entish or Old English or Classical Arabic) often used for reading ancient texts. Or, in my world, talking to really old undead. Alignment languages are another possibility that's really contentious but I kinda like the idea. At the very least, I love the idea of liturgical languages like Church Latin or cursed languages like the Black Speech of Mordor. Common languages, trade languages, non-verbal languages, secret/disguised languages, and so on are all cool variants that can be included to serve a different function rather than merely being attached to a race.

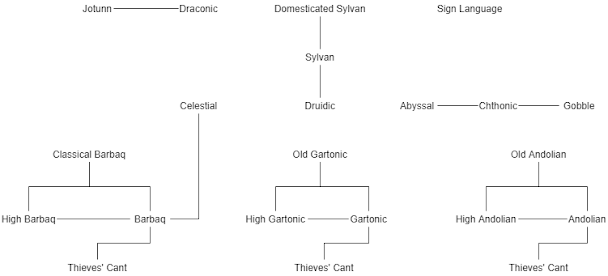

Here is the list of languages I made for my sample Brave setting that I've used in playtesting. It's inspired by the Medieval Angevin Empire, mostly in Aquitaine.

"Campaign languages. If they share a bolded letter next to them, then they’re related:

- Gartonic (French)

- Andolian (English)

- Barbaq (Arabic) A

- Chthonic (Underworld common tongue) B F

- Celestial (known to Lawful creatures blessed by the powers of Heaven) A

- Abyssal (known to Chaotic creatures connected with the powers of Hell) B

- Druidic (known to Neutral creatures spiritually attuned to the world) C

- Thieves’ Cant (a related version of Gartonic, Andolian, or Barbaq)

- Sylvan (the language of wild animals like woodland critters) C D

- Domesticated Sylvan (the language of pets and farm animals. Always whispered) D

- Sign Language (very rare and has no relations, but is universal)

- Deep Speech? Maybe. (known to aberrations)

- “Old” or “High” (antiquated or fancy version of another language, treat as related to vernacular version)

- Jotunn (known to Giants) E

- Draconic E

- Gobble (known to goblinoids, never written down in its vernacular form) F

-Dwiz

Thanks for this post, it's very cool.

ReplyDeleteI made my own version, but decided to link together *all* of the languages, so you can have a terrible game of Telephone.

Celestial H

Old/High Common: H C

Common: C

Wretch: Ratmen, goblins, etc. No written form. C W

Cheoxic: Undead. U W

Abyssal Demons U

Alshyr: Speak to blood/organs. U L

Druidic: Anti-language of druids. L P

Sylvan P B

Beast-tongue: Animals B

Draconic B A

Jotunn: Giants A

Primordial: Elementals A D

Alephtine: Machines. D

Deep Speech: Aberrations D

H Holy

C Common

W Wretched

U Unholy

L Life

P Primal

B Beasts

A Ancient

D Deep

I made an image for it but it won't let me attach it here :/