Much has been made of the weird underlying assumptions of general "liberal American capitalism" woven throughout mainstream D&D economics gameplay. It's called "anachronistic" by most and "great unique setting flavor" by the generous (usually in regards to

Greyhawk or the implied setting of OD&D). It's an artifact of D&D's 1970s American Midwest origins and is, ultimately, probably useful for the same reasons that it was inevitable: it agrees with all the most common assumptions the general audience will have about economics going in. It makes the game more accessible and simple. Following from this is where we get "Gold for XP," a rule whose utilities I'm sure I don't need to expand on here.

But I like worldbuilding. I like when I learn new information and then get to use it as a DM. I also like when I learn new information and have to use it as a player. So "alternative economics" are inevitably going to interest me as a potential design space. The most common alternative that people explore when addressing D&D's inexplicable "industrialized free market" is to attempt to gamify feudalism or include provisions for bartering. I, too, will be addressing those in this series. But I'll be doing a lot more, as well.

Strap in.

Why Do This?

Regular readers will know that I like gamifying economics a bit more than most folks in this hobby. I don't ever really get carried away, of course. I'm not trying to turn D&D into

EVE: Online or anything. But I often advocate a little sprinkle of crunch here or there inspired by ideas in economic theory that can spice up your gameplay, like by having a

currency exchange fee at each new settlement or

limiting item availability by settlement size and whatnot.

See, the thing that scares most people about "gamifying economics" is either 1) turning D&D into accounting homework, or 2) being forced to roleplay shopping encounters. Both of these things suck, I agree. But there are plenty of ways to flesh out the economics of your game without adding nitty gritty granularity and number crunching nor ever bogging things down with a lame improv sketch unrelated to the actual point of what anyone here is trying to accomplish.

The key is that economic systems and tools are really just ways of constructing choice architecture, which is what all of our gaming is built out of. Schemes for organizing decisions in interesting and dynamic ways, including resource management, tradeoffs, incentives, perception and hidden information, availability, substitutions, and all that good stuff, is literally the heart of game theory. Any part of the game where decisions are being made by players is a part of the game where those decisions can be made at least a little bit more interesting. As a guy who doesn't want to handle too much crunch in his gaming, I nonetheless insist that you can still expand or tweak your game's economics in manageable ways that will pay off. This is what we'll be talking about in Parts 1 and 2.

Additionally, economics is oftentimes our most familiar battlefield for acquiring our goals. Most RPGs take it as an unquestionable assumption that the long-term point of the game is to somehow advance. You attain power or prestige or whatever rewards the players can be motivated to chase. The traditional XP-for-Gold system is one of the most tried-and-true methods of this, and was originally created with the intention of being fully woven into domain-level play. Thus, much of what follows will also be proposals for entire campaign structures inspired by economic arcs found throughout historical societies, because I find them to often be more novel and interesting than the simple, "Greyhawk-megadungeon rugged-individualism rags-to-riches" arc that characterizes OSR play. This is what we'll be talking about in Part 3.

My Goal Here

The standard assumptions that we're challenging here are numerous. A coinage economy with a stable, standardized currency. A free market that seemingly exists in isolation. "Off the shelf" adventuring goods (implying industrialized manufacturing). And so on. What follows from here will be a series of economic ideas used or theorized throughout history that don't fit the standard assumptions people use when playing in D&D, but could make for a cool addition or substitute. Some of them are entire alternative economic models while others are merely specific financial devices that are unfamiliar to people nowadays. I encourage you to not go overboard in introducing your players to a completely bizarre and exotic, holistic view of "unorthodox economy" for your worldbuilding. Less is more. Just one or two unfamiliar features will have a memorable impact and improve gameplay just that extra little bit we're looking for, so pick out a couple favorites from what I list below.

Table of contents for this post

I wouldn't necessarily recommend skipping ahead though, since I continuously build off of each piece.

- Markets Without "Money"

- Gift Economies

- Rationing

- Credit

- Interlude: So Where Does Money Come From?

- Money, But Weird

- Pseudo Bartering

- Paper Money/Cheques

- Boulder Money

- Cowrie Shell Money

- Cryptocurrency

- Fantasy Money

Markets Without "Money"

This is a bit of an in-depth topic, but I'm going to give it an overview first because, once introduced, it'll allow us to look at lots and lots of simple ideas I really want to tell you about.

There is an almost universal misconception that the history of commerce goes: "first bartering, then money, now credit." This is known to historians and anthropologists to be completely false. In fact, it's actually totally backwards from how things normally progress. Believe it or not, a "true" bartering system has never existed.

The idea comes to us from Adam Smith, who I don't believe intended to misinform anyone here. He was merely conjecturing on "why does money even exist" because it was a natural question to ask in his pursuit of a better understanding of how money is used. And when you define money as "a medium of exchange" then it seems only logical that, before it was invented, markets must have just been for trading goods and services directly. And the "barter system" he describes has so many flaws in it that it seems like money is an inevitable invention to fix it!

Except that money took a few thousand years to be invented, so whatever flaws it's the solution to must be flaws that you can nonetheless live with for a few thousand years. But the flaws of the barter system are so fucking bad that it wouldn't even last a week before everyone figures out it doesn't work.

|

| Yeah, yeah. This shit again. |

It typically relies on what they call "the double coincidence of wants." If I have a chicken but I want a beer, and you have a beer but want a chicken, then we're in luck! But if nobody with beer wants a chicken, I'm screwed. And even if you have a really big market with lots and lots of people, you'll still have this problem fairly often.

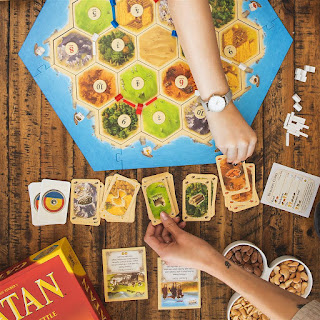

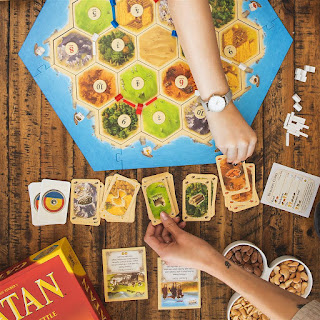

Like, have you ever played Settlers of Catan? First of all, it kinda sucks. I know, I know. It's the "introduction to good board games" board game. It'll blow your mind if you've only ever played Battleship and RISK. But you quickly discover it kinda sucks and there are much better games. More importantly, have you ever played Catan and been completely stuck with a hand of resources that no one else wants for, like, 3 or 4 turns? Sure, eventually the situation will change. But in the real life equivalent of that situation, you'd starve to death first. And have you ever tried continuing a game of Catan well past the point where a player has attained victory? That right there is one of the best little hands-on simulations of "why bartering systems are fucking unusable" a regular person could try out and understand in an evening.

I'm going to gently redirect our attention away from using bartering in RPGs (for now).

Instead, pre-money societies seemed to use either 1) gift economies, 2) rationing, or 3) some kind of reciprocal credit system. Or a combination.

Gift Economies: a gift economy is one where goods and services are given without any explicit expectation or negotiation for a reward. Of course, in order for society to function, people will end up pretty much always gifting back in return, but there's just a ton of leeway. There's a staggering diversity in the forms that gift economies can take, so it's hard to describe them "in general." One of the best efforts I've seen was Chris Gregory highlighting a few specific qualities that set many gift exchange economies apart from what we're used to with our commodity exchange economy:

- Commodities are immediately exchanged whereas gifts have delayed exchange

- Commodity goods are alienable whereas gifts are inalienable (i.e. they'll forever be associated with the gift-giver as their one true "source," and, in some sense, their eternal owner)

- Commodity exchange actors are independent but gift exchange actors are dependent

- Commodity economies are all about quantitative exchanges whereas gift economies are about qualitative exchanges

- Commodity exchange is thought of as between the objects whereas the focus of gift exchange is between the people

Of course, many have countered that these aren't actually the two, diametrically-opposed possibilities that Gregory makes it out to be. Tons of examples exist of things mixing and matching traits here or including other traits, so it's more fruitful to look at specific, unique examples of them and see what neat possibilities can be found therein.

One of the most famous ethnographies on a gift economy was written by Laura Bohannan about the Tiv people of Nigeria. When she first showed up and got a house, before she really had a grasp on the language, the locals immediately started giving her gifts. Lots of food and supplies and whatnot. Being a good anthropologist, she writes all of this down but doesn't know what it means. A local finally explains to her the situation: "people are giving these as 'gifts' but you have to give something back. Figure out what they're worth, but the key is that you cannot give something back of equal value. Whatever you give back must be either greater in value or lesser in value." What's the deal with this? Well, the idea is that gift exchange is the foundation of nearly all social interaction in this culture. Reciprocating a gift exchange to a neighbor is your excuse for visiting them and being friendly. As long as you are in debt to gift a friend or they're in debt to gift you, then you always have a reason to see each other again. The goal is to maintain a perpetual debt. It's actually quite rude to give a gift of equal value, because that's interpreted as you saying that you never want to have anything to do with this person again. It's kind of funny, because the Tiv have a really hard time understanding the idea that you might just want to visit a friend without any material expectations. Sometimes you just want to keep up with your buddies, you know? On the other hand, it's quite wholesome that their culture has found a way to ensure that everyone always has a means of having their needs met and in an explicitly friendly way, where debts are not traps but instead invitations. A debt is an expression of care in this culture.

Thinking about how to gamify that, what I find interesting is that the items you receive in life are chosen by others. You don't have control over what you're given, and it's not unlikely that you'll receive food you dislike or equipment you have no use for. Imagine in an RPG receiving randomized equipment at the start of each adventure, each item donated by a friendly NPC. From there on out, the PCs' main way of acquiring new equipment would not be in collecting treasure and making purchases off an item menu at market. Instead, they'd have to seek out friendly relationships with specific NPCs. I could see this working well in a campaign focused on a small, tight-knit community. Maybe a village in a Points of Light setting. The PCs each have a roster of NPCs and what kind of general supplies each one has. Based on that, the PCs collect "treasure" during their adventures that they think would make for good gifts for specific NPCs that they want stuff from. It doesn't have to be useful to the NPC, but maybe appropriate gifts will have a better chance of being reciprocated with more useful adventuring equipment. For example, let's say you really want some fancy armor. Well, you'll have to receive them as gifts from the town armorer. What does he like? If you find out that he's a big drinker, then it sounds like your next adventure should be a booze heist.

This scheme would seamlessly merge both the economics of your D&D game with the social and political landscape, which would ground your players in the setting and help them form meaningful relationships with your NPCs. Even the worst murderhobo will care about an NPC if they can see the material benefit of keeping them as a friend. It would be fruitful for each PC (or maybe the whole party as one) to maintain a visual roster of all the NPCs in their village, what each one provides, what each one wants, and the current state of their debt relationship to the PCs.

Rationing: I err on the side of calling it "rationing" rather than a "planned economy" because there's an occasional misconception that "well, ackchyually, ancient societies were all communist" and that's just a pretty misrepresentative and politically-motivated statement. That said, some of the more expansive and centralized governments rationed to an extent that could fairly be described as a command economy.

It kind of makes sense. Imagine you're either a hunter-gatherer society or an early agrarian society. Survival is difficult and growth takes a long time. Why bother with the risks of a market? You don't have the luxury of surplus goods to let resources circulate without a plan. The only way you ensure everyone has their basic needs met is by setting the rule that all crops and kills are gathered at one place and then rationed out evenly. And you have to ensure everyone has their basic needs met because your fledgling tribe is fragile enough that no member is expendable. It's not necessarily equal or worker-owned like communism, it's just the bare minimum to keep things afloat.

|

"Don't worry homie, the basics are covered

for you. You just do the rest." |

Of course, some societies continued this well past the point where it was "necessary." Ancient Egypt, for most of its history, had a tightly-controlled command economy even though they had such a surplus of so many types of goods that their trade exports made them fabulously wealthy. [At this scale, historians call it a "palace economy"] They did eventually use coinage, but for a long time before that they still valued things in silver-defined pricing even without ever actually

using silver money. They just grew wealthy enough to allow for an internal barter market to emerge among their citizens, who would trade their government-rationed resources with each other using the silver-based prices. But again, this isn't truly a "barter economy" because barter is not the means by which people's needs are met. The palace's rationing is. The bartering that follows is essentially just kids trading lunch items at the cafeteria because, hey, little Alice likes fruit snacks but not pudding and Bobby likes pudding but not fruit snacks.

To me, the most gameable idea here is to just simplify things for your players and tell them, "don't worry, basic supplies are covered before you set out on an adventure." You can still have them track their supply of food and water, but they don't have to worry about paying for it. In fact, if their designated labor role was to be the "adventurers" of the tribe, consider what kinds of resources the state would probably think is necessary to ration out to them. Maybe armor, arrows, and candles come in their standard ration kit too.

This is actually like the "anti-choice" option, if you want to remove some economics crunch from default D&D. Just consider the worldbuilding implications of this rule: the players must be citizens of a government that handles all this rationing. They must be part of a community who they have some reason to give back to. Their basic needs are met, but only if they're loyal and useful to their home community. Choosing to rebel is choosing to switch to the survival genre.

Credit: you know how a long-term bar tab works? You just order your drink even if you don't have the money for it, then the bartender keeps track of how much you owe, and you pay it back later. Now imagine if you "paid it back" when they come around to your auto shop and get repairs done.

Now that doesn't sound too different from the shitty bartering system I described. But imagine, 1) you have some kind of consistently-defined value system for everything, even if you're not actually using coinage money, and 2) everybody just had a "bar tab" open with everyone else all the time. Let me explain:

In medieval England up through the 1700s, about 97% of all transactions in a typical village were by credit. Partly there wasn't enough money around and partly because people didn't like the connotations of using money with your neighbors. Neighbors are supposed to be friends who trust each other and want to keep the community going strong, and a credit system reinforces that mutual trust. So everyone just kept track in their heads of what they owed others and who owed them what. Then, every 6 or maybe 12 months they'd hold a "communal reckoning." Everybody gathers together and then lays out in full all the debts between everyone in town. You identify matching debts and chains of debts and whatnot and you cancel them out. "If Alice owes Bob, Bob owes Charles, and Charles owes Alice, then we can cancel that out." You cancel and cancel and cancel until you can simplify it down to whatever small debts remain that couldn't be canceled with anything. "Okay, so it looks like it's just Charles who owes Debbie three dollars still." And then they settle those last debts and are now reset to 0. They have a clean slate for the next 6-12 months.

High-trust markets allow you to ask for something and know that you can delay your "payment." Everyone trusts that their neighbors will help them out later. It's the foreigners who you have to request payment from either up-front or immediately following the sale. They're unfamiliar to you and quite possibly won't be seen again. Or when the settlement grows too large it may become unfeasible for everyone in town to know and remember and have a personal relationship with everyone else in town.

|

How it feels returning from the dungeon to

distribute the spoils of adventure to all your neighbors |

Using this in D&D would look quite similar to the gift economy idea I described above. The main difference I envision is the order in which things happen. Instead of the players giving gifts to NPCs in order to obtain adventure supplies, they just take the adventure supplies they need and then pay back the NPCs later somehow. Once the cycle gets going though, there isn't much difference. Presumably, the gift economy has a lot of randomly-rolled equipment because the NPCs are choosing what they want to give as gifts, while the credit economy has the PCs choose what they want specifically. And just like in real life credit economies, having a "money" system to set values for goods and services is still useful. Every time the players "buy" something at market, they just take what they want and write down the costs as debt.

How do they pay back their debt? Well like I said, a credit economy assumes that each person is contributing to the community. You don't worry about taking as much as you need because, presumably, people are taking advantage of whatever good or service you offer enough that it'll roughly even out. So what good or service do the PCs offer? Well, traditionally it must be "adventure." In order for adventuring to be your means of making a living in this economy, then by definition it must be something valued by the other villagers enough that it can clear your debts with them. In traditional D&D, your motivation to adventure can be entirely selfish. You gain your own magic items and forgotten lore and treasure. The treasure is only of value to the nearby communities in as much as they'll accept your coinage at market. But this economy doesn't use coinage, so what can you bring home from your adventure that's helpful to folks here?

Well, as in the gift economy, maybe it can be as simple as choosing your adventures such that you acquire things that will be of value to the specific NPCs you want to buy stuff from. There is no economic gameplay, there are only personal sidequests and favors.

But maybe "adventure itself" can be thought of as valuable to the community. Maybe you're the designated defenders of the village, who drive back the hordes of monsters emerging from all the ruins and regularly attacking the NPCs. As long as you bring back a trophy from each monster or boss, the village leaders might declare that those trophies can be counted as payments on your debts. So instead of maintaining an individual tab with each business owner, you just have a general ongoing debt to the whole community that you're paying back with each trophy brought home, evidence of your efforts to keep them safe.

An Interlude: So Where Does Money Come From?

Well like I mentioned before, these schemes all really only work for high-trust environments. They're very communal. It's when you get large populations and/or lots of strangers traveling to and from your community that these systems break down. Anthropologist David Graeber posits that money first arises to meet the needs of armies. Specifically, the kinds of large-scale traveling armies of the earliest empires. I would argue that the evidence more points to the cause being "expansive states" in general, not just military expansion. But also, yes, mostly military expansion. It's a simple thing to have a town militia or garrison defend your city-state and be just another citizen of the community. But if your aspirations are to conquer abroad or deploy troops across wide stretches of home territory to campaign against an invading force, then suddenly your army is put into that very tenuous position of being a big pile of strangers everywhere they go.

You

have to supply your armies if you don't want them to pillage your own countryside, because then what's even the point. But supply trains are a logistical nightmare. Ancient armies did indeed deal with them and often faced the task of devising the optimal setup, but a really simple alternative is to just have your soldiers buy their supplies from the settlements they're visiting. Rather than going to such pains to bring food to them and have it travel alongside them, just have your armies come to the place where food is found. They can't establish credit or gift relationships with the locals they meet, but if they give them money and then the king says, "that money has value and you guys should use it at home among yourselves" then suddenly, wow! A passing army giving you money actually has value!

From there you get plenty of benefits. Larger-scale economic activity, more easily taxable subjects, an easy means of disseminating propaganda to reinforce your kingly authority, etc. Of course, some commodities make for better money than others. Gold is usually chosen because 1) it doesn't tarnish, 2) it didn't have a ton of utility to pre-industrial societies compared to other metals (unlike today, where it has lots of uses), and 3) while heavy, it can be made into small, easily-carried coins. Silver is similar but is slightly worse and a good bit more common, thus making it the obvious tier beneath gold.

Contrast this with, say, cows. Cows make for terrible money. They have a natural lifespan, unlike gold. You want to milk them or eat them or make something from their body parts, unlike gold. And they're a pain in the ass to transport, keep alive, and divide into smaller increments, unlike gold.

Other metals didn't work. Aluminum was extremely difficult to extract, lead is too heavy (and toxic!), iron was too useful, as was copper and tin, and so on. Another reason silver isn't quite as good for currency as gold is because it looks like most other metals. Isn't it crazy that, like, gold is just inexplicably yellow colored? Talk about a convenient signifier of value.

But of course, vanilla D&D uses gold money. Let's talk about other possibilities.

Money, But Weird

Pseudo Bartering: earlier I mentioned that Adam Smith's lineage of money was backwards. Not only did credit precede money, but as you'll now see, bartering follows from money!

Specifically, barter economies almost always arise among societies that are used to dealing with money but, for one reason or another, don't currently have access to money. Oftentimes it's because they simply don't know any other system, and other times it's because they're still subject to the same conditions that make money useful to begin with. Two common situations where barter markets emerge are collapsed economies where runaway hyperinflation has ruined the value of official money, as well as prison economies. The thing is, what makes it a barter economy and not just another type of commodity money is that the new form of money is still intrinsically useful. Some folks think of bottlecaps from Fallout but that's not really a barter system, that's just a substitute for gold. The kinds of markets I'm talking about will use something like cigarettes or alcohol as the medium of exchange.

This is highly gameable in D&D because it creates a tradeoff choice for the players. Do we spend our money or use our money? In order to have the same granularity as gold pieces do in D&D, the utility of any one piece of this barter medium should be small. Salt is a good example. If you're a Roman soldier given your salary of salt, is that you being paid in currency or is that you being rationed a basic supply? [spoilers, it's neither because that never actually happened]. Can we come up with more? Imagine, I don't know, health potions that you can control exactly how much you drink from. Each 1 HP of potion has the same market value as 1 gp if traded.

Smarter examples than that include lumes from Patrick Stuart's Veins of the Earth. One of the best ideas in the whole book, "lumes" are a mechanic he proposes that would merge money (the silver piece standard, in this case), time, and light supply. Thus, 1 lume = 1 sp = 1 hour of candlelight = 1 hour's distance traveled. This all makes sense for an Underdark setting. Down here, light supply is the most valuable thing, so anybody anywhere would gladly accept it as payment for items. At the same time though, the PCs need it and will be draining 1 lume per hour as they hexcrawl through the dark. It's incredibly elegant.

A similar idea I've come up with is to apply the same thing to

cinnabryl from the "Savage Coast" region of the classic

Mystara setting. If you're not familiar, the Savage Coast was a mini-setting released for AD&D in a supplement called

Red Steel that features a bunch of pirate-y content. There's a terrible plague on the land called the "Red Curse" that slowly mutates you the longer you spend there, until eventually you're reduced to a shambling beast. One of its main gimmicks, from which it takes its name, is the special substance of "cinnabryl" (kind of like a metallic

cinnabar). Having cinnabryl on your person prevents the curse from affecting you, but its power gets spent in the process.

Thus, we have a good metal for coinage that everyone in this country really wants. You could probably pay for anything with cinnabryl, but you never want to give away your whole supply because, hey, you need it too. In fact, you need a constant supply of it because it depletes over time.

This is a bit of a simplication. In reality, the "Red Curse" mutations would start out positive and grant you new powers, and the cinnabryl wasn't useless when spent. It turned into "red steel" which still weighed less than steel and counted as magical when used as a weapon. But I'm streamlining here. Something comparable to cinnabryl is a great idea of a hybrid barter-money commodity.

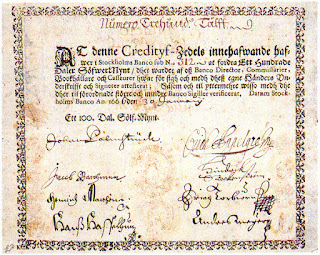

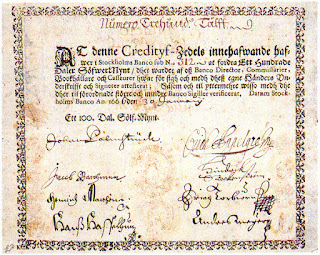

Paper Money/Cheques: okay, so by the time paper money became ubiquitous, it became pretty much the same experience as using commodity money from the individual consumer's point of view. Don't get me wrong, from an economics perspective, there are massive differences between trading gold coins directly and trading gold-backed paper bills issued by a bank. But for the PCs, a fully-adopted paper money system isn't going to have a meaningful difference in gameplay. So I would argue that the most interesting characteristics we can find with "paper money" for gameplay inspiration is the form it took on in its earliest days. The situation I'm about to describe was roughly the same both when paper money was first being introduced in China and in England (I've heard Carthage used bank promissory notes too, but I don't know much about them).

So you go to the bank and you drop off some coins. They hold it in their storage and they give you a receipt. This receipt functions as an IOU. When you return to the bank and hand them this, they should give that amount of coins, right?

So what if you paid for goods or services by giving the other person this IOU instead of coins? I mean, the receipt doesn't have a name on it. Anyone could go to the bank with that piece of paper and trade it in for the stated amount.

Of course, I think you can imagine how the logical consequence of this was people only trading in the paper IOUs and never bothering with the coin withdrawal. But like I said, let's stick to the parts early on. In this world, 99% of people still deal only in coinage, so the PCs ultimately need cold hard metallic cash as their reward if they actually want to buy new gear. Who deals with bank receipts then? Merchants, naturally. The guys who use banks. It's a novel type of treasure/macguffin: in exchange for rescuing (or robbing) a merchant on the road, the players get a bank note. It does them no good now, but it's really just a quest hook they literally hold in their hands: take a journey to the closest bank to cash this in. If it's for a huge amount, then that's not unlike any other treasure-hunting quest full of adventure.

Bank notes take up less inventory space than coinage because they're just paper, but they're also less liquid. No need to haul something around in a cart and keep it safe, but you probably can't spend the note itself for anything unless you meet a merchant. Although here's my favorite idea:

Before national, centralized banks became a thing, each private bank would issue its own bank notes! Thus, which bank notes you can cash in depends on your relationship to each of the banks. That's faction play right there, baby. Imagine a rising late medieval kingdom with three major banks, each of which is one of the most powerful institutions in the country. Merge these with your existing factions, like having one be a mercenary company, another a wizard's college, and another a thieve's guild. But in addition to all that normal juicy faction gameplay, each one also has a special type of unique treasure in circulation throughout the kingdom in the form of these IOUs. If the players ever come into ownership of one, they either go to cash it in (if it's a friendly faction) or trade it to a merchant NPC for something (if it's an unfriendly faction.)

Boulder Money: this one fucking rules.

The native inhabitants of the Yap islands in Micronesia used to use a currency called Rai Stones (sometimes called "Fei stones") that take the form of massive stone boulders carved in the shape of a wheel. The largest is about 12 feet in diameter and weighs 8,800 lbs, although some are as small as 1.4 inches in diameter. There are around 6000 stones in total.

What the fuck, right?

The way it worked is that everyone in the community just maintained a collective oral memory of who owned which stones. They were almost always too heavy to ever move, so you'd just "pay" for something by saying, "I'll give you the stone up on Clay Hill for it" or "how about you give me the stone under the bridge and the stone on Turtle Island and we'll call it even?" Every stone had a history of owners that you'd memorize when you came into ownership of it so you could recount the full record. Nice little bonus is that they're literally immune to theft because ownership has nothing to do with physical possession.

This system worked so well that, one time, a group of fellas bringing a stone home on their boat from overseas accidentally lost it in the sea during a storm, but... everyone still used it anyway. After all, you never need to hold or even see a boulder for it to be used, so everyone just remembered it as "the stone out in the ocean." Who knows if it's even still there?

I know it sounds bonkers at first but it makes a lot more sense than you'd think. Rai Stones are an extremely stable commodity, both physically and economically. One of the cons of commodity money is that it's based on scarcity and is, thus, subject to variation on the commodity's supply. But the number of boulders generally stays the same.

It doesn't need to be mobile like gold or silver because no one's going anywhere. They live on an island. No armies or trade or nothing to worry about. It's even closer than you think. Eventually, in the early modern period when European commodity money was in the form of gold but the stockpiles of gold grew too large to carry around, it instead just got deposited into vaults. The money became stationary and the people dealing in it just started "paying" each other in bank receipts that allows a person access to that money. So, honestly, almost just like boulder money.

Oddly enough, the biggest difference between boulder money and early modern gold money isn't actually size and weight and all that. It's just how the supply is managed and distributed: is it communal and oral and memorized or is it recorded on receipts and IOUs?

For an RPG, you could also explore the idea of stipulating on "which" money you own, not just "how much." ...Kind of like an NFT, in a way?

In real life, different stones had different values based on size and craftsmanship. Personally, I think it would be much more gameable to just make them all equal. The easiest and probably most interesting way to incorporate a mechanic inspired by rai stones is to adapt them directly. The next time you play an island adventure like

Hot Springs Island or

Neverland, imagine if every hex on the map had 1 stone, and that's what got "traded" around. Your current money is tracked directly on the map. In the corner of every hex, the DM has written down the current owner. The only treasures that you're questing for in dungeons are direct resources and magic items, but money is only ever something that just sits stationary in each hex somewhere.

My brother pointed out to me how interesting it is that they're also called "fei" stones. Imagine if the fey traded in a menhir currency. It sure would reinforce how unfamiliar and weird they are to most players. In a similar fashion, I would map my faerie otherworld with a menhir on every hex, but the current owner also affects the random encounters and weather and stuff of that hex. Fey have a supernatural influence on the world around them, and ownership of menhirs is also a direct force of power you feed into the world.

Substitute fey for dragons if you'd like. They clearly don't collect gold coins with the intention of spending them, so maybe they use something else for money.

Cowrie Shell Money: shells are probably the one commodity used as money as frequently as gold, if not more so. Throughout history,

tons of cultures have used them. Ancient China, West Africa during the slave trade, south Asia, various Indigenous Americans groups, various Oceanian cultures, etc. What makes it distinct?

Well, like gold it's durable and small and kinda useless but pretty. It's nearly impossible to counterfeit though, and it's hard enough to acquire that you probably won't risk inflation. But from the point of view of a PC? I honestly don't see any ways in which it can be meaningfully distinct from gold coins. The real reason to use shell money in your game is just worldbuilding flavor, keeping in mind that rather than "exotic" it should really be treated as fairly normal and mainstream, as it was in much of the world for most of history.

The only idea I can come up with is if the shells in question were harvested from giant monster snails instead, so that aspiring adventurers might go monster hunting instead of gold mining when they want to get the raw form of the commodity directly.

Cryptocurrency: Yes, we're really going there. Crypto may be a nonsense scam for naïve and pitiful men but, mechanically speaking, it does have some interesting properties. But because most of its unique features can't really be replicated through some mundane analogy, we are faced with the inevitable worldbuilding implications: the D&D equivalent of Cryptocurrency is "Wizard Money." Which I find a hilarious idea. Imagine Gandalf as a Crypto Bro.

The convenient thing is that both the "Proof of Work" and "Proof of Stake" processes are really easily gameable. Let's try to imagine the most straightforward translation of these ideas into a fantasy context.

Imagine a magocratic city-state. In the center of town is an Elemental Nexus. The local wizards have devised a way to generate new matter from it by performing complex rituals with it. It's a perfect alchemy engine, able to produce whatever they want. And just like real-life alchemists, the potential they see in this is, inevitably, a means of making new gold so they can get rich.

Wizard spellbooks are full of figures and diagrams for a reason. Arcane magic is mathematical. It's all about manipulating the forces underlying reality in calculated ways, switching variables here and there to get the results desired while keeping the equation balanced. But you can't just plug in whatever data you want: the algorithms are too complex and interwoven for you to get away with adding in a couple zeros where you want without the rest of the pieces of the machine conflicting with this.

Thus, these mathematical rituals require fresh, complicated-yet-natural data each day. And what better way to instruct the nexus to produce gold than to "input" gold? So they meticulously track every gold coin transaction that happens in the town market each day, and then they "verify" those transactions by inputting all of them into a new ritual that they run through the Elemental. Once they've accomplished this, the Elemental spits out new gold from thin air, and is permanently tattooed with all the transactions that were just fed into it. Thus, every day there is a new competition between all the Gold Wizards to see who can perform the ritual first in order to trigger the Elemental to generate new gold for them, and a perfect, permanent ledger of transactions is formed on its elemental form.

Oh, and it's also slowly killing the Elemental and destabilizing reality around it. Because of course it is. Proof of Work is a fucking nightmare. Of course, I understand that the idea behind Proof of Work is to be a consensus-building security measure, and that the generation of new Bitcoin after each verification is just a side incentive to get people to participate. Maybe that's how this wizard practice started too? But just as in real life, inevitably it would become entirely about the daily bounty to be won.

As for Proof of Stake, things are a little less outright destructive and a little more gamble-y.

Proof of Stake as an alternative consensus mechanism requires each validator to put up some collateral money, which becomes your percentage chance of being the one awarded the bounty once the next round of transactions are validated. So you can imagine an alternative version where each wizard dumps a pile of gold into the Elemental each day and one of them gets their amount back plus some extra, like a big lottery. That could be a fun minigame for a PC to indulge in.

Fantasy Money

I promised economic content inspired by real-world history, and indeed that is the bulk of this post. But it was inevitable that we talk about some bizarre, imaginary stuff. I polled the NSR Discord server for what they've come across before in addition to the stuff I've seen and used.

First of all,

of course I've run a goblin market. That is practically the reason I play D&D. And when you go to goblin market and buy weird goblin goods, you don't pay in money. I only offered my players 12 items to purchase but gave each one a unique price. And of course, each one was either very folklore-y ("a lock of hair," "a piece of your shadow," "a bit of luck" i.e. your next nat 20) or something awful that makes goblins laugh ("the live sacrifice of an innocent" or "ten random minutes of your life where you'll be switched out with a goblin"). This was very much a novelty that I can't see running a whole game on, but it was incredibly fun. In fact, it might have been the one and only time in my life that a "shopping session" was

actually made fun somehow.

The D&D 5E adventure

Descent into Avernus, which takes place in Hell, features a special currency that doubles as a magic item called "soul coins." They have a few cool traits. The lore is that they're literally creature's souls bound into a coin, which is something that devils like to trade. My favorite idea is that they're slightly

alignment-restricted. Evil characters can carry as much as they want while non-Evil characters can only carry a number of coins up to their Constitution modifier before incurring penalties to their checks and whatnot. But the main crunchy bits are good ol' modern D&D magic item complexity. "A

soul coin has 3 charges. A creature carrying the coin can use its action to expend 1 charge from a soul coin and use it to do one of the following:"

- Drain life, i.e. gain 1d10 temp HP

- Query, i.e. ask the coin's soul a single question, drawing from the knowledge it had in life

That is, if you ask me, quite a potent little magic item. I can hardly imagine every coin in my wallet having those traits. but one or two would be a neat thing to steal.

Meanwhile, in the Old World of Darkness game Wraith: the Oblivion, everything is ghosts. PCs are ghosts, NPCs they're trading with are ghosts, and all items and currency are constructed out of ghosts. Yes, the ghosts being used as building materials and money are suffering. The whole thing is fucked. The main mechanical comsequence I can imagine for this is that, if you're strapped for cash, then you can always tear a bit of yourself off and use that as money. Not sure what I would make the consequence, though.

A user by the name of Xag told me about their post-apocalyptic game where the main currency was monster teeth. This is a much better version of the idea I had for cowrie shells above. The problem with that idea is that 1) cowrie shells are a good equivalent to coinage because they're tiny, but 2) the only way to make it actually an "adventure" to acquire them in the way I described is by fighting giant mollusk monsters, and thus their shells would be huge. Well, Xag solved that problem: giant monsters still typically have coin-sized teeth. I like games with monster harvesting and crafting systems, and it seems a sensible thing to me that, in addition to getting food and crafting materials off of its body, you can also extract a literal money reward.

And above all else, there's just a wealth of evidence here that economics is an opportunity for worldbuilding. Even if you insist on keeping things just like vanilla D&D in function, why not take this chance to reinforce the world's cultures and fantastic properties in small places like money? I'd like to thank "That's Wondeerful!" (boy howdy what a username) for the following brainstormed ideas:

- "strings of beads, starting with common materials like wood and moving up to glass, and perhaps with the most valuable being carved from gems and stone like jadeite"

- "trading wood carvings of animal heads"

- "underground wizard societies is trading talismans, like the mummified fingers and hands of more powerful wizards and saints"

- "spices could be traded" [presumably as a direct currency rather than a trade good, as in the real world. They continue:] In an ideal world for me, people would be bartering with vials of funky and weird smelling and tasting powders and liquids"

- "Perhaps people could trade with pieces of something with meaningful cultural significance, like the roofing off of a cathedral that burned down"

- "currency in the form of fancy knots, like macrame or something adjacent? There's maybe a handful of people who know the actual practice of creating these piece of fiber art that are used to exchange goods"

All of those tell us more about a culture than the "gold dragons" or "silver shards" of Waterdeep's money.

Conclusion

I hope one or several of those inspired some neats ideas for you. If not, don't worry, I have more to come. Sometimes it's less about money itself and instead how you use money. That said, keep in mind what I've covered in this post, since much of it will come up again in the next two parts of this series.

If anyone has any additions to this post, I'd love to hear about it in the comments. Better yet, can you come up with an alternative to conventional money that would present unique gameplay opportunities? Nothing is off limits, it just takes a little bit of imagination.

-Dwiz

1. If any Wizard were a cryptobro, it'd be Saran. His whole character is not as smart as he thinks he is and full of hot air.

ReplyDelete2. Honestly the best implementation of blockchain append only currency are the rai stones mentioned above. That's exactly how it works. What happens when two influential families disagree on who owns what stone? Is a fork just a civil war?

3. A good example of the pseudobartering mught be military bullets from the Metro videogames. A collapsed society where you can buy supplies with high quality prewar ammo, but its also the best ammo to help you survive.

*Saruman

DeleteI agree all around. I wish I had brought up the implications of blockchain forking because that's brilliant.

DeleteGreat post, thanks.

ReplyDeleteWas there hack money (hackgeld) where guys would just wear silver jewelry, like torcs, and they would just break parts off to give to people? What if treasure was just in items (vases, necklaces, bracelets, pots, etc) and to pay you break it up? Maybe works the same but just flavourful.

Also maybe herding societies could just use animals as money. Not sure how to gamify this.

Around this, what if it was just assumed that basic adventuring equipment could be made by the adventurers? e.g. a tribal type society where each warrior just makes their own bows, spears, slings, clubs, shields, etc. They can also make cloth armour, or leather armour out of whatever animal they can kill.

Last one, which I am sure you will appreciate, there is a bit in Buffy the Vampire Slayer series where Spike and a bunch of demons are gambling for kittens!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKPqLxWD8qA

Awesome.

I've not heard of any such hack money and I'm skeptical of it ever coming into existence just for a few reasons of impracticality. Jewelry is typically worth more than its component materials because of the time and labor it took to craft, which is quite considerable. Making jewelry only to break it later seems like a really expensive waste of productivity. The closest thing I can think of that remains practical would be the system in historical East Asia where coins would be strung along a length of cord, which is why Chinese coins have the hole in the middle. This isn't ever really worn like a necklace or bracelet, but it certainly COULD be, which is a great idea.

DeleteAlthough what you describe has also been used in at least one other place I've seen. Check out this post from r/worldbuilding: https://www.reddit.com/r/worldbuilding/comments/cva3hl/glimmers_a_currency_designed_to_be_snapped_in_half/

Simply captivating little piece of worldbuilding right there, and it avoids the issue I just brought up because the broken pieces of the jewelry can easily re-unite on contact.

Those other ideas definitely mesh well with the "pre-civilization, points of light" style game that most of the rest of this post seems to encourage as well. PCs making their own gear sounds to me like substituting economics gameplay for crafting gameplay entirely. Which I'm not necessarily opposed to, I should mention.

Also thank you so much for reminding me of that scene. I had forgotten about it over the years. What a show.

I had to go looking for some links to see if I had imagined it. This is what I was thinking of:

Deletehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hacksilver

http://nms.scran.ac.uk/database/record.php?usi=000-190-004-111-C

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305440321001424

It seems like it was used for a long time but we're not really sure how it was used.

What about spanish pieces of eight?

DeleteThese are good points. Sounds like my intuition was wrong. Even better!

DeleteAwesome post! Only complain I have is that you missed the opportunity on the title "Boulder Money: this one fucking rock.".

ReplyDeleteGreat writeup in this and your other articles in the series, really goes into a lot of detail on some very interesting ideas that gets the gears in my mind turning as to how to apply them. I've always used something like a barter system in my games, but this is definitely introducing some new perspectives on it. Is it alright if I link to you in a blog post on the subject?

ReplyDeletePlease do! I'm glad you enjoyed the series and I'd love to see what you might do with it!

DeleteThanks! I posted it here:

Deletehttps://tales-of-the-lunar-lands.blogspot.com/2022/05/on-barter.html

It's really just some ideas as to how barter can be implemented in gameplay, but you really made me think more about how the system could be applied.

Hello Dwiz we'd really like to translate this article into French on our (free) site ptgptb.fr - the best of the Internet RPG, translated for the French-speaking audience - could you please contact us so that we'll send you our engagements ? :)

ReplyDeleteInsofar as I understand, livestock are actually a fantastic and widely-used form of wealth. They are of near-universal value, grow in value with time investment (since living beings reproduce), are self-locomotive and thus actually very easy to transport, and often produce secondary products which form a stream of more granular revenue.

ReplyDeleteFor those reasons they were a pretty common medium of high-level exchange, and were very often the most desirable treasure for our world's best analogies to "adventurers" (bands of warrior-youths, brigands, raiding parties, etc.).