I have

previously talked at length about the virtues of "campaign-level play." That is, rather than only ever running your game as a series of mostly-isolated scenarios in episodic fashion and then

calling it a "campaign," you actually flesh out all the connective tissue between adventures. There are certain gameplay structures you can incorporate which aren't really interacted with on a scenario-to-scenario basis, but which nonetheless have an impact on the campaign

as a whole. Examples I give are things like a calendar and downtime play, usable maps and travel gameplay, complicated NPC relationship charts that'll change over time, and of course, domain play and some slightly more in-depth economics than just a menu of regular adventuring gear.

Most of this post's contents will be schemes describing entire economies and how they function. There was a bit of that in Part 1, but it rarely extended beyond small communities. Everything here will be stuff that works at the scale of whole kingdoms, and oftentimes is most effective when contrasted against neighboring kingdoms which don't share these traits. If nothing else, it's decently educational for folks who find this stuff interesting and it's very often good worldbuilding fuel.

A common theme for these is new choices that players can make to acquire or use their rewards. The classic options are 1) go on an adventure where treasure is found, or 2) get paid treasure to go on an adventure. The former is self-directed, the latter is NPC-directed. Sometimes the DM will offer other avenues of gaining rewards though, like running a modest business in downtime, gambling, or swearing patronage to a demon lord in exchange for dark power. I think players should have a buffet of these options to indulge in at their own discretion. But to do that, you need novel options. Well this post expands that list and complicates a lot of what was already on it.

Table of contents for this post

Since each section is pretty big and you might feel like skipping some. These are roughly ordered from shortest to longest.

- Mercantilism

- Rentier Economies

- Sparta's Economy

- Medieval Islamic Economics

- Cuba's Economy

- Guilds

- Other Neat Stuff

Mercantilism

Mercantilism is an economic political philosophy that enjoyed popularity in the European great powers from the 15th century to the 18th century when they were really getting into that imperialism game we all know and love. It's pretty weird to someone accustomed to the modern perspectives of international trade. I'll do my best to describe it here:

First, we assume that all states are in perpetual economic war. It's a zero-sum game and the goal of a state is to enjoy economic power over everyone else. The goal is to counterintuitively use trade to become as self-sufficient as possible. I say this is counterintuitive because we would typically think of a self-sufficient country as being one that doesn't trade at all. They keep to themselves and make all their own stuff, right? But the thing is, we all know that it's nearly impossible for a country to be truly self-sufficient. So as long as some amount of trade is necessary then you can at least minimize imports and maximize exports. See, the mercantilist state doesn't really want to be left alone. They want power over the other states. All financial ventures and even many other state activities are about funneling money into your home economy and making all other states more and more dependent on you while ensuring that your state isn't dependent on anyone else. Funnily enough, this is where modern colonialism comes from. Whereas nowadays we associate imperialist expansion with the inevitable needs of free-market capitalism to grow and grow, the mercantilists were actually about as anti-free-market as they come. You create colonies solely for the purpose of feeding the mother country, forbidding them from trading with anyone else. Their purpose is to extract wealth from elsewhere and deliver it to the homeland. And when you have to import stuff, try to only ever import cheap raw materials so that their more expensive, finished forms can be made within your borders. Oh, and don't let any gold or silver leave the state once it comes in. But don't necessarily hoard it, either. Keep it in circulation so the economy is healthy, but only within our borders. The market is highly regulated in this system because it is seen as fundamentally being a vehicle to empower the state.

Where's the D&D potential?

As I see it, mostly in the kinds of quest hooks that arise with PCs who are recruited to either support or attack mercantile policies. For example, if all the great powers forbid the export of gold or silver, even as payments for their imports, but they all also want to accumulate as much of it as they can... how does anyone ever come into ownership of more gold or silver? The answer: plundering.

This was an era of lots and lots of stupid, destructive warfare. Not to mention the Golden Age of Piracy being nestled in there, too. PCs who can help support mercantile policies would probably be handsomely rewarded by their government. If their quests can bring lots of gold, silver, and raw materials into the economy that wasn't there before (either from other countries or from old ruins and the Underdark and such) then maybe there could be a bounty reward for it. Most quests would take place in someone else's territory, implying an added danger: getting home back across the border without the other side's authorities stopping you.

This could actually simplify a lot of the hiccups in trying to incorporate trade goods into D&D economics. Lots of folks think it would be a cool and atmospheric thing to include more, but then you run into problems. When the players find casks of palm oil instead of gold pieces in the dungeon, then they have to add the extra step of selling it to the right buyer. That's how boring shopping sessions happen. But what if there's just a royal treasury that will directly buy trade goods off the PCs for slightly more than their market value, no questions asked?

Conversely, maybe the royal treasury is the only buyer the PCs are legally able to sell their goods to, but there are lots of foreign buyers who would pay more for it. Then, whenever the PCs finish a quest and haul their treasure home, they have to make one last decision: do we get its normal value nice and simple or do we try getting a much higher value but risk getting caught and punished by our government? Sounds like a decent time for a die roll.

Of course, all this trade restriction also means that there's inevitably a huge black market. I highly encourage introducing a secondary equipment list of "black market goods" into your game, just in general. This can work especially well if your campaign takes place on a borderland region, as is so classic a setting for D&D fantasy. Let's imagine your Keep on the Borderlands or West Marches hometown has a market, and its government is quite mercantilist. There are foreign merchants in the city who you buy your goods from, but the government has a daily or weekly cap on the amount of items that the PCs are allowed to buy at market. They don't want those foreign merchants draining away too much gold from the economy, you see. But the Dungeon Master will let them buy more items beyond that... for double the price. That's the black market, baby.

Oh, and if it wasn't yet clear: mercantilism is a terrible economic philosophy. Turns out trade is not a zero-sum game, and that it's kind of ridiculous to think so. It's also just incredibly difficult to pull off. Mercantilist colonies rarely ever managed to break even on the costs of investment. So even if all you care about is getting rich and lording over everyone else, it's not even an effective strategy for doing so.

Rentier Economies

Related to mercantilism, according to many theorists, is the idea of a rentier economy. Rent-based wealth is when you make money from someone without actually producing anything or contributing to production. Typically, it might be by charging somebody for the opportunity to do something you control. Obviously, most of us think of renting a home or renting a car. But it also describes all kinds of economic activity. A company lobbying the government for subsidies is engaging in rent-seeking, technically. Ticket scalping is another good example: making a profit without actually contributing anything to the economy. Whereas wages are earned through labor, rent is just a reward for owning something.

Economists from nearly all philosophies have almost always unanimously agreed that rent is the worst form of wealth. Even Adam Smith was like, "fuck landlords, all my homies hate landlords." To quote Wikipedia:

Rent-seeking is the effort to increase one's share of existing wealth without creating new wealth. Rent-seeking results in reduced economic efficiency through misallocation of resources, reduced wealth-creation, lost government revenue, heightened income inequality, and potential national decline.

Okay, now imagine if an entire country built its economy on that.

Rentier economies are most commonly associated with the modern day Middle East and North Africa. Most people know that a lot of Gulf countries rely heavily on their natural abundance of oil. But what they probably don't realize is just how ridiculously profitable their oil industries are. No, really, even more profitable than that. While they still usually extract, produce, and distribute the oil themselves, the amount of work being done isn't exactly proportional to the thing being produced. Thus, economists instead classify it as fitting the definition of rent-seeking better: for barely lifting a finger (relatively speaking), they receive fabulous wealth... essentially for the luck of happening to own the oil fields.

And sometimes it's taken further. Sometimes they literally rent the oil fields to outsiders. After all, oil extraction and production is really expensive and difficult. While you could do it yourself and then charge your buyers more for the oil you're selling... fuckit, they seem more than happy to do it themselves. They seem to like keeping their own citizens employed, so why not let them work on your land? Let them worry about paying workers and having labor standards and all that annoying stuff. It's a bit riskier but even more profitable.

To varying degrees throughout the last century, oil-based rentier states in the Middle East and North Africa have included Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Qatar, Libya and Algeria. It's also happened to some countries in Latin America and Central Africa as well, since they also have lots of oil and natural resources that bring in enough wealth from foreigners that their economies don't require regular forms of productivity, skilled labor, or services. You can also rent out things other than natural resources. Egypt and Jordan have strategic value to the US because of their geographic locations, so you better believe they charge the US military rent to operate bases there.

Egyptian economist (and one-time interim Prime Minister) Hazem Beblawi defines rentier economies by these qualities:

- Rent situations are predominate among the economy. That means that, somehow, more wealth is circulated by rent than by actual production of goods and/or services. Which is insane.

- The economy relies mostly on external rent. So it's not citizens paying rent to other citizens like we're normally used to. The whole country is the landlord for another country as the tenant.

- The generation of rent is confined to a small proportion of the state, so it's not like everyone in the country is in on this... even though it comprises most of the economy.

- It is the state’s government that receives the rent.

Quoting from a paper I wrote in college:

Because the state receives substantial wealth from its rent industry, it can use that to provide for the population without having to levy taxes. This provides a model for wealth distribution much sought-after in the socialist aspirations of Arab states looking to reject Western capitalism. But because of this, the populace becomes dependent on their government and live at their mercy, being asked of no taxations but also not being able to ask for any political representation. Thus, no pressure exists for democracy or governance derived from the consent of the governed. This is even easier for citizens to buy into if the state is encouraging nationalist sentiments. The main source of pressure from the population would instead come from a market failure where the rent industry begins failing. This is practically a self-fulfilling prophecy anyway, as monolithic economies are intrinsically unstable.

No taxes? Can you imagine? That's so weird to me. In fact, many of these countries' modern governments began as a means to distribute rent wealth to the population, so you actually get paid to be a citizen (sometimes in the form of shares in the government oil industry).

So yeah, it sounds nice for the citizenry at first but it's actually another terrible and unstable economic philosophy. Taxes create a mutual relationship between citizens and their government, and it's only a matter of time before the money faucet goes dry. But if we were to gamify it, let's imagine starting out with the "rationing" model I described in Part 1. So there's no taxation, and the government even gives you money as a citizen. Because almost all wealth in the economy is acquired through the rented industry and everyone's needs are met by the universal basic income, then the only reason people do other forms of business is either tradition or to make a little extra. But if your farm busts, then you aren't screwed and the economy won't feel a thing. Meanwhile though, there's lots of foreigners on your country's land who are doing all the production. Almost all natives work in the public sector and almost all foreigners work in the private sector.

This sounds like a country of wizards to me. The native population has the luxury of time and their needs already met, so they can focus their attention on higher-minded things like science and philosophy and magic. But they have a tense relationship with the dwarves who they rent their main natural resource to, and occasional conflict with the elves who they charge rent for the military base they own on this land.

Players in such a state either don't have to worry about money (another "anti-choice" if you want to remove the drive for treasure-acquisition and money quibbling) or they get rewards from the government for locating new caches of the natural resource their state rents out. Alternatively, the government might revoke your UBI as a punishment, using it as leverage over you.

Conversely, imagine if the PCs were outside laborers in this state rather than citizens. Then they're in a desperate grind where every means for them to make money is somehow already owned by the state, which will charge them rent for the opportunity. Imagine a wealthy noble who owns the land a dungeon is on and charges a fee for adventurers to get to plunder it. Then, dungeoncrawling becomes an even bigger gamble. Each dungeon the PCs are looking at charges varying entrance fees, which should correspond with the expected treasure haul the PCs get from it... but might not.

I should mention though that, nowadays, the "government pays the citizens the rent wealth" isn't common in most of these countries anymore. Many of them have horrifying unemployment rates and an entire generation of working-age young people, especially men, who are unemployed because of the lack of jobs even needed to sustain the rentier economy. If only a universal basic income were still the norm, then it would at least be more bearable even if the system is still unstable overall.

And also I think it's become clear that I really like the notion of hubris-filled wizards running a fucking awful economy.

How about how fighters run an economy, then?

Ancient Sparta is one of those cultures that all fantasy worldbuilders love because it's just so different from what we're used to. Even the other cultures of Ancient Greece were fascinated by how weird they were.

In the land of Laconia, there was a caste system. At the bottom were the natives, the Helots, who had been enslaved and were made to do all the hard labor. In the middle were the non-citizen inhabitants of Laconia, the Perioikoi, who lived along the coasts and highlands and who handled all commerce, business, and manufacturing. At the top were the Spartans themselves, the foreign occupiers who served as the military ruling class.

The Spartiate men were raised as warriors from a young age, and upon reaching adulthood the state issued them a plot of land and a contingent of Helots to work it. But they also had private property, able to acquire more land and slaves to become rich.

So while adult Spartan men are made to be the elites in this society, and they certainly took advantage of their position to treat everyone else horribly and assert their power, it is interesting all the ways in which they didn't have power. They were legally barred from engaging in trade or manufacturing, from owning gold and silver coins, and from traveling outside Spartan territory without explicit permission. Everyone else had those privileges, but they conflicted with the role that Spartiate men had in society. And the non-warrior Spartan women also had an upper hand economically because of their particular inheritance law.

On paper, their inheritance law is actually perfectly equal and significantly more progressive than those of their peers. When a Spartan man died, his state-issued stuff returned to the state (and would get redistributed to some other man later) but his private property went to his wife rather than his son. When the widow died, the property was distributed evenly between the kids regardless of gender.

But consider how common it is for Spartan men to die young. They are literally an entire caste of people whose whole lives are spent focusing on warfare. Many women marry young, become widows young, inherit a lot of property young, and then spend the rest of their lives building that property. Though some of it will pass to their sons, it won't take long before those sons' inheritance is given over to their own widows. Thus, all property gradually accumulates in the hands of a minority of powerful Spartan women. They were known as the "Spartan heiresses" and they held tremendous influence, often lending money to the all-male government.

If I were making a country in my game inspired by this, I'd amplify the stratifications. Each caste gets their own part of the game they get to play with, like the archetypes in Errant. Imagine this party: one player gets to do violence (the Spartan), one player gets to do politics (the heiress), one player gets to craft and do commerce (the Perioikoi), and one player is in control of 20 henchmen (the Helots) to handle everything else. Together, they have to manage one household as it faces challenges on all those fronts.

That might be a bit extreme for some folks, but the more general takeaway for regular D&D would be either 1) characters who are forbidden from participating in the game's economics and are instead rationed all their equipment, or 2) characters who have exclusive access to the game's economics and must buy and sell on the party's behalf.

Oh, and one more thing about Sparta that isn't related to economics but is still really cool: they had a Diarchy. As in, a monarchy but with two kings from two royal families, who ruled equally. It worked because one was always on campaign abroad with his armies while the other was ruling over the homeland. Bonkers, right?

Medieval Islamic Economics

As you're probably aware, when they invented that whole "Islam" thing it was a smash hit almost immediately. They went full Golden Age right out the gate. It was tight. And while many people are vaguely aware that they had lots of advancements in math and medicine and science and philosophy and all that epic gamer shit, they also had a commercial revolution. Many historians nowadays characterize it as "Islamic capitalism." In the Quran, God explicitly gives the go-ahead to trade. And I mean, the Prophet himself was a merchant, born into an especially mercantile culture and who did not approve of the state meddling with prices. The recognition and protection of private property is incredibly important in early Islamic philosophy, probably because many early Islamic philosophers were also merchants!

The Muslim world during the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates had a free market with privately-owned businesses and entrepeneurs as the primary actors. And while the state

did engage in production, it was still functionally just the private enterprise of the prince himself. They used a common currency spanning half the goddamn world, the dinar, and they innovated in serious capital accumulation through a number of means. Investing in big projects, exporting to distant buyers who'll pay more, and making merchanthood a family enterprise so your descendants inherit a head start all contributed. A huge one was the state leasing out the right to collect taxes to private contractors, who had to put their own wealth up as collateral before going out to farm taxes. And of course, kinship-based business partnerships were a major factor in establishing massive, long-lasting trade networks. A great deal of effort was put into recreating the qualities of a high-trust market on a scale you would normally think of as extremely low-trust. Just read about the

Hawala if you wanna see how far they took this.

Why? Many argue that it worked out because of a widespread legitimate reverence for Islam. It might sound unbelievable to the cynics who never trust capitalists, including myself I'll admit. But it seems as though "Islamic capitalism" functioned to serve the general welfare because it sincerely wasn't profit-motivated. Yes, business was conducted with the aim of maximizing profits, but specifically for the purpose of paying one's zakat (the obligatory charity to the needy that Muslims must pay) and funding one's hajj (the obligatory pilgrimage to Mecca), two of the Five Pillars of Islam. The Quran also explicitly forbids one of the most predatory capitalist habits of all, usury (i.e. charging interest rates on loans, or perhaps just "unreasonable" interest rates). Capitalism was seen as a mechanism for Muslims to support their fellow Muslims and uplift the whole Muslim community worldwide. The primary incentive for one to not screw over their competitor or even business partner is, "hey, we're both Muslims, aren't we? Gotta make sure my homie is taken care of."

A slightly more sophisticated explanation is that the state doesn't have to regulate the market for it to abide a common system of practices and regulations because all Muslims are following Sharia even if they live under different governments, and Sharia accounts for a lot of the factors involved in business practices.

Whereas the merchant class is often looked down upon in many societies, they enjoyed high status here. They often served as the primary diplomats of states and used a lot of their profits to fund other folks' pilgrimages. Banks, contract lawyers, and financial speculators all also gained the same kind of prominence we see them have today.

So in many ways, this actually functions very similarly to the "default D&D economics" we're used to. The whole "why is Greyhawk a Libertarian paradise?" thing is just the actual reality here. Even the kings are just business owners, and everything runs on gold acquisition. That said, I see a few interesting opportunities here to incorporate into D&D.

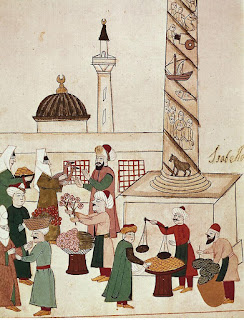

- PCs as merchants. This definitely has the most potential here and I feel kind of out of my depth attempting to cover it in this article. One of the most celebrated instances of a game fleshing this out is Luka Rejec's Ultraviolet Grasslands, in which the players are part of a traveling caravan in a great Dying Earth-plus-Oregon Trail style pointcrawl. One of the first choices they make is "why are we doing this?" which sets the XP scheme for the campaign, and one of the common options is "to make money."

Provide the party with a financier that loans them €1d10 x 1,000 for their first caravan (creating a debt). Gain 1d6 x 100 xp for every new profitable trade route discovered, and again for every new profitable trade completed.

He expands on this mechanically from there. Look at this page:

I would call that a refreshingly rules-lite way of letting players actually be merchants. And don't worry, we're going to revisit merchants later in this very post. - PCs as tax collectors. You're a private contractor working for the state. You need some wealth to get started, because you put up a minimum amount as collateral in case the collection goes poorly. Then, you go out and travel the lands collecting taxes from all the citizens. Once you've collected enough to equal your collateral, start taking a cut as personal profit and deliver the rest to the state. It's a good excuse for a party of adventurers to be on the road all the time, and merely traveling the kingdom tends to present opportunities for adventure. But maybe the collection part itself can be made an adventure. Maybe a community is refusing to pay, or maybe another community had all of its gold stolen by a dragon. Whatever the complication, it's the PCs' job to get that gold in the hands of the king by whatever means necessary. And best of all, the longer the campaign goes, the more wealth the party accumulates and is hauling around with them, and therefore, the bigger a target they are for bandits and villains.

- Kinship Structures: this is a flexible idea that can be applied in all kinds of ways throughout the game. I've considered writing about it as its own post. One of the most persistent social structures in human history, but which is nearly absent from mainstream D&D, is the idea of everyone belonging to a tribal identity of some kind. The closest thing we tend to play around with is "race," which I'm sure you know is a pretty flawed game device. But large tribal groups are the most important social grouping used in many societies, (notably for our purposes here: Arabs). "Tribe" is a familial structure that sits at a level above mere family or even a clan, big enough that a single tribe likely spans multiple settlements. This map shows Arab tribes in Arabia, but it's a bit tricky. Some are huge because they have claim over large areas of mostly-uninhabited desert. Meanwhile, Yemen is densely packed with tribes because it has vegetation. But of course, a mercantile society will have lots of movement going on, so whatever settlement you're in will have members of many tribes. Thus, the simplest way I see to gamify this would be to just establish somewhere from 7 to 12 tribal groups in your setting, almost entirely superficial and without mechanical distinction, and attach one of them as a label to each and every character who appears. Then, you automatically get a bonus here or there with NPCs who match your tribe. Hell, you could assign them to a die and roll randomly! Make 10 tribes, assign each one a number, and when you meet a merchant on the road just roll a d10 to see what tribe they're from. Each PC has a lucky number they're hoping for so they can get a bonus on reaction rolls or lower prices or something. Maybe combine it with the Ultraviolet Grasslands caravan rules I just described so there's a small extra modifier that can possibly make a trade route more valuable. And of course, you can use weighted dice when in a settlement. "In the hometown of Alpha Tribe, an NPC will be an Alphan on a roll of 1-6 on a d10, and will only be an outsider Tribe member on a roll of 7-10."

Of course, I want to note before moving on that I still don't believe the dominant narrative here should be taken at face value. I am incredibly skeptical that a widespread system of free market capitalism could have existed that worked as harmoniously as many scholars claim. Because, y'know, incentivizing exploitation and corruption is literally intrinsic to capitalism. While nearly every piece of literature I found on the subject was quite insistent that the Golden Age of Islam achieved "good capitalism," I noticed another thing that none of them mentioned: the fact that early Arab Muslim conquerors were literally the folks who invented the African slave trade. That's right, they set up trade with West African kingdoms to kidnap and enslave innocent people to be bought by the Muslim ruling class for the purpose of exploiting them for labor. While many of the agrarian laborers were being paid in the Muslim world, there were also chattel slavery plantations invented in this same time and place, all-too-similar to the kind most of us are familiar with from the historical American south. Of course capitalism sounds ideal when you conveniently leave out all the people suffering from it the most. While I concede that it may be possible to actually sustain a long-term capitalist system without the constant instability and market crises that characterize it in its modern, industrialized form... the damage done to the invisible populations of history is more than enough for us to be critical of the system as a whole.

Cuba's Economy

So what if we pivot to communism instead?

I can already tell there'll be some tension over this one, but I have to include it because Cuba has the weirdest economy of any country on Earth, bar none. This is mostly because of the aforementioned communism, but there are lots of contributing factors. It'll take awhile to explain, and while I'm leaving a lot out, I want to be sure to include each weird piece that I can come up with a way to gamify.

First of all, Cuba is a communist country. Or rather, it has a Soviet-style administrative planned economy where almost everyone is employed by the state somehow. Most academics insist on splitting hairs when it comes to this, for valid reasons. As I'm sure you know, this kind of system is usually very unstable in an industrialized society (christ, what kind of economy isn't unstable??).

During the Cold War, they largely got by with the support of the Soviet Union. However, they've managed to keep it going since 1991 due to three things:

- Concessions on their communism, allowing for worker cooperatives, self-employment, foreign direct investment, and other characteristics of market economies and even a small degree of privatisation.

- Absolutely batshit policies that no other economists would ever consider.

- Genuinely reconfiguring their economy towards its strengths and being persistent.

So let's talk about some of what makes Cuba unique.

1. The Embargo

|

| Everything is 50s pastel-colored. I like all the pink. |

Or as they call it in Cuba, "the blockade." The US imposed an embargo on trade with Cuba that's still in effect. Not only does it forbid or strongly penalize American companies from doing business in Cuba, it also forbids any foreign companies from doing business with the US if they also do business in Cuba. And as you can imagine, pretty much every country chooses the US over Cuba.

As a result, Cuba is like a time capsule from the 1950s. Nearly all of the cars are from then and have just been meticulously maintained this whole time. I've heard there's some company that specializes in manufacturing new replacement parts for those 50s cars specifically for the Cuban market. There are some Soviet cars and motorcycles but they're considered even worse quality than American cars made 70 years ago.

They generally have to accept inferior quality for anything they import, which is a lot (general rule of thumb with island countries, by the way). Things that are an American specialty are really rare. You can't easily get beef in any form, and believe it or not, the typical penalty for an unsanctioned killing of a cow is a longer jail sentence than for fucking murder.

2. Cash-only economy

No credit cards here, buddy. All commerce is in cash, and they pay all their international debts in cash. This has given them the bizarrely archaic problem of not having enough liquidity to do what they need to do. They are trapped in debt because of the international neoliberal financial order, like many developing countries. And one of the many reasons they can't consistently make their payments is because they literally don't have enough money. As a result, much of their economy is shaped around trying to funnel foreign cash into their economy just to build up the supply of hard currency reserves, which gets depleted as soon as they have to make a debt payment.

This also makes day-to-day financial transactions a bit weird. Oddly enough, I actually had to practice going back to only dealing in cash for the 2 weeks leading up to my trip there because I lost my debit card and had to order a new one. But while that can be inconvenient for a consumer, it sure is fucking weird for a business owner. For example, their government cannot conduct audits on more than a handful of businesses per year. Why? Because they have to literally do it by hand. The way it works is that all businesses are in sort of an "anti-lottery." A handful will get randomly selected each year to be audited, a guy is then sent in, and he has to count up all your cash and transaction records manually. The only real pressure to be on your best behavior is that it could be you that gets audited this year. You never know, but... you could probably get away with a lot of fraudulent activity, to be honest.

3. Two official currencies

They are the only country in the world with this dubious distinction and it is so fucking weird like you have no idea. It kind of makes sense when you hear where it comes from but holy shit is it a bad idea.

So they didn't have enough cash once the Cold War ended, right? Previously their main industry had been exporting sugar and sugar products like rum. That was never very profitable to begin with, though. They decided to make tourism their main industry so they could bring foreign capital in, and they came up with a weird but kinda smart scheme on the side: they'd start accepting US dollars from tourists for everything. When I was there, 1 USD was equivalent to about 25 Cuban pesos. However... even though the US dollar had so much more value than the Cuban peso, tourists would still pay the same number price for things as Cubans were, just in a different currency. For example, a hamburger at a restaurant might be listed as costing "3." A Cuban buying it pays 3 pesos, while a tourist buying it pays 3 USD. In this way, the profits of all businesses frequented by tourists would skyrocket, and the tourists would still be usually getting fairly cheap prices compared to what they pay for things at home (since the economy is so rough here that everything is crazy cheap). And remember that all these businesses are owned by the government, so even though business owners are getting a ton of revenue in USD, they hand it all over to the government who then pays out Cuban pesos to all the citizens as part of the planned economy.

This was called "dollarization" and it was working out until the

Bush junior administration retaliated. They escalated the embargo by adding regulations keeping people from using USD in Cuba without a special license, plus added punishments to international banks that distribute USD to Cuba.

So, with it no longer viable to use USD, what did they do?

Well,

Fidel said, "fuckit" and decided to improvise: create a replacement currency that would be equivalent to the USD in all ways except for the government issuing it, and which would serve the same purpose. The economists who came up with the dollarization strategy were like, "we are in way too deep with this now to just give up on it" and found a way to persist despite not being able to use dollars.

The result is the

Cuban Convertible Peso,

abbreviated as

CUC (pronounced "kook," very fun to say). The native currency, the

Cuban Peso, is abbreviated

CUP (pronounced "koop"). CUC is a currency that can

only be used within Cuba and by tourists, and whose value is directly indexed to the value of the USD so that they're always equivalent. The idea is that tourists come in with their USD, get it exchanged at a government-operated kiosk for CUC, and then use that to pay for everything during their stay. Behind the scenes, the government would continue their process of collecting all that USD and using it to pay their debts.

It is, without exaggeration, the same system as going to a Chuck E. Cheese and converting your real money into special arcade coins.

Well, it's a bit more complicated. They charge a tax on the exchange rate (foreshadowing for later in this post!) because of the inconvenience, so most tourists actually come in with Euros or Canadian dollars and convert that to CUC so they don't lose money. Even Americans visiting Cuba will take their USD and turn it into Euros at home real quick before then turning it into CUC once in Cuba. Did I mention yet what a spectacularly bad idea this whole system is? Especially for a country that is trying to build its economy on tourism, an industry focused entirely on offering convenience and stress-relief to its customers? And get this: the most ill-conceived part of all, and the easiest to fix, is that tourists doing the currency exchange will only be given the largest bills available. So I came in with the equivalent of 300 USD to turn into CUC, and I was handed three 100 CUC bills. But guess what? No tourist business on the island has enough liquidity to break a hundred dollar bill. I had to have all my meals paid for by my friends for the first 3 days I was there until I finally broke down and bought a fuckton of tourist garbage just so I could break a hundred and get, like, 20 dollars back (still a hefty-sized bill for most businesses to handle). This was a problem for everyone I was with. Many times we'd all go out to eat together, rack up a bill close to a hundred dollars, and then have one person pay for the whole thing just so they could get some small bills. The next meal we ate, it was someone else's turn to cover everyone, and so on.

I brought home a hand-made chess set, domino set, and bongo drums though, which is nice I guess.

While writing this post I learned that they finally dropped the 2nd currency in 2021, after about a decade of claiming that they were going to make the transition "by next year." Not sure how much of this post that changes but we're moving forward with the weird version because that's what I know about. I commend Cuba for finally fixing this problem, but I admittedly find problems to be more interesting to think about than... things that work just fine, I guess?

4. Black Market: A black market is any economic activity that's noncompliant with the state or market institution's rules. In places like the US, this would describe things like prostitution and drugs. But in a command economy, it would describe literally any and all transactions not specifically approved of by the state through the normal mechanisms of government-salaries and ration cards and whatnot. So any time a Cuban uses their remittance money or tips from tourists to buy an extra ice cream cone or a new pair of shoes, that's technically black market activity. And this is so ubiquitous, so thoroughly integrated in everyday life, that the government's economists simply accept it and run with it. Thus, Cuba manages to have the very strange quality of an "unofficial official black market" that they incorporate into all economic planning as a matter of course. When it comes to this type of "surface level crime," no one is ever punished for this, with the country instead relying on it as a supplemental market to boost the economy on top of the underlying command economy that provides everyone with the basics. That said, there are some things that are truly illegal. Cuban citizens were introduced to Wi-Fi a few years ago. As a communist country, their internet is pretty censored and segregated, not unlike China's. But when I was asking a Cuban college student what he does for fun, he let slip that he's been watching The Mandalorian and The Witcher.

"Wait, what? But I thought you couldn't get Disney+ or Netflix."

"Oh, right. Well, yeah. But we have el paquete."

I confirmed with many, many other people that this is a very common thing there.

"The Package" is a terabyte of digital media that you can buy from your local Package Dealer each week, downloading it from them onto your hard drive that you take home. Every week you get a fresh collection of popular entertainment from around the world. Most people wipe their hard drive every week to make room for the next week's package, so there's little permanency. That said, you can sometimes download just one or two things you want for a much smaller price. Binge-able TV shows are popular, whereas weekly-releases are really inconvenient. A guy I met said that he missed the first couple episodes of

The Mandalorian and won't be able to catch up because the Package Dealer doesn't hold onto previous weeks' collections. He'd just have to wait like 6 months until a new Package is released that has the full series included.

No one knows exactly where the Package comes from, but it's kind of inevitable given the situation. Some people think the government is secretly involved though, because the Package conveniently excludes anti-Cuban media as well as all pornography. So once again, "unofficial official black market."

Other characteristics of the modern Cuban economy:

- Remittances: most Cubans rely heavily on remittances from family members abroad. Lots of old Cuban folks in Florida send money to their relatives back in Cuba even though they cannot themselves return. When you receive remittances, you get it in the form of CUC, which vastly inflates your wealth. While it's necessary for attracting foreign capital into Cuba, it's contributing to a growing inequality between those Cubans with relatives abroad and those without. It especially benefits white Cubans, whose family abroad often thrives whereas those Cubans who are, y'know, descended from enslaved peoples don't have the same support system. That said, the majority of the population is receiving remittances and are living on them.

- Services over Goods: services now make up about 81% of the economy's exports, focusing on tourism/travel-related services, education, telecommunication, construction, sports, tech shit, and most of all, healthcare. Cuba has 8.4 physicians per 1000 people, the highest in the world. For reference, the UK has 5.8, Germany has 4.3, and the US has 2.6.

- Segregated Economy: for a long time, many businesses and even physical areas of the country were designated as tourist-only or native-only. Regular Cubans legally couldn't use tourist-designated hotels because they'd be taking a spot away from a foreigner who would be injecting fresh money into the economy. Nice restaurants, beaches, and other luxury spots weren't just expensive: they are literally segregated from the native population's lives no matter how wealthy they get. The only exception is if you're going to those places as an employee, in which case you're obviously not getting to take advantage of them as a consumer. This was helpful to making dollarization work: the easiest way to have two separate currencies in circulation is to just have them be used in two entirely separate markets. This was often called "tourist apartheid," a pretty dramatic and inaccurate name, but it was kinda shitty. They got rid of it, thankfully. That said, all the nice tourist shit is still prohibitively expensive.

|

| Here's an example |

Multi-generation Houses: so after the revolution, the government guaranteed that everyone would have housing. Did they then embark on a massive construction project of new houses? No, that shit's hard and expensive. Instead, they seized the houses of all the rich people and said, "we're turning these into apartments" (still offering the rich people to stay if they'd like, which they of course all rejected). I'm sure some new construction happened, but for the most part they achieved universal housing by using what was already there. But what do you do when the population grows? Isn't land development for residential areas inevitable? Not if Castro has anything to say about it! Every family has a house, so when you have kids then they never move out. When they get married and have kids, you suddenly have three generations under one roof. It goes on and on like this. What do you do when things get cramped? Why, just build more floors, obviously. Many, possibly most, of the houses you'll find in Cuba have either new additional shoddy levels built on top of what was once the roof, or possibly they took existing levels of the building and installed a floor halfway up, thus splitting it into two levels. Or both.- Social Programs: Despite all the difficulty and occasional authoritarian oppression, one massive thing in Cuba's favor is that their citizenry enjoys nearly universal housing, employment, education, and healthcare. For those of us who consider those things to be a right, this is something I really don't want to downplay.

So that's a lot, right? I hope it was interesting on its own, but I know that you want your D&D gameables. So what do you take from this?

Well, you could try to recreate the entire system as a package deal, but more likely you could take bits and pieces here and there that seem interesting. Let's tackle each of these one by one and think about how you'd translate them into a gameplay situation:

- Embargo: easy. Take your exploration-age Renaissance country and put it right next to a country operating at the level of technology of Ancient Greece. Introduce a much harsher equipment list and only allow nice things like health potions and navigation gear to be bought at massive markups, if at all. Replace all the weapons and armor in this country with bronze (weapons lose 1 Quality when maximum damage is rolled while armor loses 1 Quality when hit by a die of max damage). Possibly give the PCs the chance to be the smugglers themselves. Repurpose that merchant caravan ruleset from Ultraviolet Grasslands but make it only for goods banned by the embargo.

- Cash-Only: this is already how D&D usually works. It's only really weird to us.

- Two Currencies: later in this post I've actually covered the idea of using separate currencies in your game, but this is specifically using two separate currencies alongside each other. My recommendation? Don't. It didn't work for Cuba and it won't work for your game. Yes, it's fascinating, especially as a bad idea rather than a good idea... but sometimes an idea can be so bad that it won't make for a good or interesting challenge to introduce to your game. At best you might flavor things with this detail as part of the country's worldbuilding, simply saying that the PCs are always using Currency A while the NPCs are always using Currency B but never burdening the players with having to navigate it.

- Black Market: well, I've already talked about this a fair amount. I don't know what the fantasy equivalent of "the Package" would be. Maybe illegal spell scroll distributors?

- Remittances: diasporas are just a generally under-utilized worldbuilding trope. The PCs could be on either side of the equation and it would be interesting. Maybe they receive a bit of free money every month from some family members abroad or maybe they have to drain a bit of their treasure income every month to be sent to their family members back home. A small bonus treasure source for your PCs or a small treasure expense for your PCs, to be used as best fits your game.

- Services over Goods: have less artisan NPCs and a lot more NPCs who provide a service. In fact, add more services to your equipment list! My own game Brave added a ton of services to the item list in Knave because players spend money on stuff other than stuff.

- Segregated Economy: you should have adventurer-only businesses. Each settlement has a district that is just for adventurers. The inns accommodate their specific needs, the stores around there deal in adventurer-specialty goods, and the cultural traditions all center around the adventurer experience. PCs only interface with the natives who are specifically employed in the "adventurer-service industry" unless they sneak into the other parts of town. Everything outside the adventurer district is way cheaper and the people are more authentic (either positively or negatively, depending on their opinion of outsiders), but once again: carries the risk of getting caught by authorities. Pretty common recurring theme in this post.

- Multi-generation Houses: For one thing, more RPGs should have multi-generation mechanics. I'm tired of always using Pendragon as my example. It would be awesome to play an RPG with a legacy system where each player controls multiple successive generations of PCs who each inherit the glory and rewards of their ancestors. Domain play can be stretched across decades or centuries as the family works to construct bigger and bigger castles and cathedrals and build on their base. And just as each PC controls a family and owns their own ancestral castle, each floor is associated with a PC/generation who built it up in their image. Eventually every player has a huge, janked-up tower that's ugly and eclectic and oozing with history. Someone make this game or find a way to put it into D&D.

- Social Programs: once again, removing challenges rather than introducing them is more of a non-choice addition to your game. This is not always a bad thing. Sometimes you need to streamline tedious areas so that you can put more focus on other areas that are important. Not every RPG should have survival gameplay, y'know? So giving the PCs universal housing, employment, education, and healthcare would be a huge simplication of things. That said, I feel like the way a lot of modern gamers run their campaigns still ends up handwaving all the lodging, literacy rates, and between-adventure healing anyway...

One last thing to mention before moving on: I'm sure you're noticing at this point that taxes are not as inevitable as Ben Franklin told us they are. And being that a lack of taxation is a distinguishing trait of several economic schemes (both in this article and in Part 1), maybe the way to properly stress that is to include some light taxation in your "default" economic models. Income tax, sales tax, property tax, and poll taxes are the most familiar to us. I think a simple sales tax is the easiest one to use, saying that, "a small proportion of the price of every item you buy is actually going to taxes" and then giving the PCs a 10% discount on purchases whenever they manage to shop in a tax-free market. If they have a lot of shopping to do, it might be an incentive to travel further just to seek out that kingdom where they can avoid the taxman.

Fantasy fans all know what a guild is, right? It's a group of players in an MMO who all go on raids together and help each other level up faster, duh.

Haha. Alright, so the reality of guilds is actually pretty obscure and kinda neat. They have a long history and appear in many contexts, including to this day. We'll talk about the classic medieval European guild as our baseline.

A guild is a collection of artisans sharing the same craft who oversee their industry in an economy and "collectively monopolize" it. Typically, the guild is granted by the local ruler the privilege of their members having exclusive right to conduct the business of that craft. For example, if the guild of vintners (wine makers) has the king's permission in this city, then only registered and trained members of the vintners' guild are legally allowed to make and sell wine in this city. But outside of this city, wine is fair game for anyone to take a swing at it. Guilds are historically tied to the rise of the middle class, money economies, and urbanization, so consider that as you try to tie them into your worldbuilding.

In modern times there's a habit of trying to compare guilds to trade unions, but that's a pretty shaky analogy. They're a lot closer to cartels. Interpreted generously, the purpose of a guild is to enforce standards and to create a living, healthy tradition of the craft. Guild members all have to go through a professional training process that takes several years:

- First, you do an apprenticeship under an older guild master. You live with them and their family and they show you the craft. You do a lot of the busywork and in exchange they give you room and board. They probably treat you like family, even though your relationship is a professional one and you signed a 7-year contract with them and probably paid to be accepted. Apprenticeships usually start when you're between 10 and 15 years old.

- Once your contract is done, you can't become a master yet until you have more experience working as a professional. Some will continue working with a master, now for pay. But eventually, becoming a journeyman is the norm. For a period of 3 years and a day you journey around from town to town and spend a few months working at different workshops. So for example, when you arrive in town you meet up with a guild representative and they hand you a list of workshops in town for your craft. You go to one, ask to work there for a few months, form a contract, and go out to celebrate that night with a bunch of the local guild members. Then you work until your contract is over, your name gets added to the local guild chapter's records, and you get a certificate verifying your good work and good conduct during this leg of your journey. Lastly, the guild gives you a bit of money to live on during the time that you spend traveling to the next town where you'll be working. You'll almost certainly be unmarried, childless, and debt-free during this time.

- Finally, once you have enough experience, if you pay a sum of money and produce a "masterpiece" of your craft, then you can finally become a guild master and an official member. Other guild masters judge your masterpiece, and if they deem it worthy then it passes into guild ownership and is put on display in a special room of the guild hall in your town. Otherwise, you might be stuck as a journeyman forever. Guild masters start their own workshop that they live in and operate out of. You can take on apprentices but you also have to pay dues ("gild") to the guild to continue being a member. Most masters who are doing well for themselves will have multiple apprentices at a time.

From the consumer's point of view, a guild is good because it ensures a standard of quality that requires skill and experience. The craftsmen also can collectively bargain with... the king, I guess? I mean, sure. There are some situations where that can be important.

|

Here's a fun game: try to find a group portrait of a guild

where they don't look like they clearly just got caught red-handed |

...On the other hand, guilds are kinda the reason we have antitrust laws. This shit is incredibly subject to corruption. Price fixing and stifling innovation were some of the big criticisms of the time. Not to mention that the barrier to entry in a guild field was a pretty major contributor to classist, racist, and sexist stratifications in society. If powerful guild masters don't like you, then you can be blacklisted from ever performing your trained skill of choice for the rest of your life. No women, immigrants, or pagans allowed to do business in

this city, buckaroo.

In short, guilds were eventually hated by both capitalists and Marxists. But, y'know. They're interesting.

I'm going to also talk about the role of guilds in politics. Don't worry, we'll explore the impact it can have on economic gameplay, but bear with me. Eventually, most medieval cities had guildhalls. Sometimes each individual guild would have its own building in the city, and sometimes the city would have one grand guildhall with a separate trophy room for each guild's masterpieces. Some places, like London, had both. These were the places where meetings were held, records were kept, regulations were decided, members were inducted, portraits of great masters were hung, maybe celebrations were held, and so on. Their prominence as civic institutions eventually led to guilds being a major player in most municipal politics.

Most famous is probably the City of London (i.e. medieval London that now sits in the center of the modern day city we call London) with its "livery companies," the collection of chartered guilds that were incorporated into the city's government. I'm going to vastly simplify things and also note that the system has changed a lot over time: on the surface, it looks like each office of government is a simple duty elected, either directly or indirectly, by the residents. You have a Lord Mayor, some Sheriffs, a Council of Aldermen, and a few other things all working together to govern the city. But either by law or by custom, all of it actually gets controlled by guilds. The chief spokesman of the guilds became the Mayor, the leading delegates of the guilds became the Aldermen, and the other members of the guilds became the burghers (i.e. residents with citizen status). Like, yes, technically the Alderman of each of the city's wards is elected by the individual residents of that ward. But you also only get freeman status if a guild grants it to you, and that's what makes you a voter. The Mayor is elected by the Aldermen, but you can't be the Mayor without first serving as a Sheriff, which are elected by the guilds.

Let's compare this to the influence of guilds on the politics of medieval Italy. From Wikipedia:

In Florence, Italy, there were seven to twelve "greater guilds" and fourteen "lesser guilds" the most important of the greater guilds was that for judges and notaries, who handled the legal business of all the other guilds and often served as an arbitrator of disputes. Other greater guilds include the wool, silk, and the money changers' guilds ... doctors, druggists, and furriers.

...

Florence was governed by a council called the signoria, which consisted of nine men. The head of the signoria was the gonfaloniere, who was chosen every two months in a lottery, as was his signoria. To be eligible, one had to have sound finances, no arrears or bankruptcies, he had to be older than thirty, had to be a member of Florence's seven main guilds (merchant traders, bankers, two clothe guilds, and judges). The lottery was often pre-determined, and the results were usually favourable to influential families. The roster of names in the lottery were replaced every five years.

Eventually they were

divided into three tiers, with fancy Italian names. You can also get creative with what a guild's craft is.

In Germany there was a guild for poets, songwriters, and musicians.

If I were stealing from this for D&D (which I have, a couple times), then I'd streamline it somehow. The complexity isn't what makes it interesting, it's the factional play. Just make it something like, "the city council is made up of a representative from each of the major guilds" or maybe, "the city council has a representative from each city ward, but only guild members have voting power" or something like that. The point is that trying to influence the outcome of an election or a policy proposal in a city-state government would require the PCs to curry favor with different guilds, each one having a quest hook. And while "fetching more supplies" or "rescuing our members in peril" are ever-popular faction quests, the one thing all guilds want all the time is more territory. "Get the king to grant us a guild patent for that city over there so we can finally have a monopoly there." This is especially juicy if there are multiple guilds of the same craft in competition. "Currently the assholes in the Sorcery Guild have a patent from the king to conduct magic here, but we in the Warlock's Guild want that spot."

In addition to PCs influencing guilds for political gameplay, why not also give the PCs a big discount or maybe even free equipment from each guild they befriend? Hell, go crazy and let them pick out a magic item from a small selection out of the guild's collection of masterpieces. I like to run my sandbox with a big public quest board as a jumping off point, and a good start would be to offer one quest from each major guild in the city. And make them the kinds of guilds that have something to offer the PCs. I'll be the first to admit that "cloth dyers" aren't terribly exciting for an adventurer, but armourers, apothecaries, innkeepers, and maybe some magical things like spellbook-crafters are definitely businesses that an adventurer wants to be on good terms with.

|

| Typical merchant flexing his luxuries |

Surely you've also noticed by now that many of these guilds clearly are not artisans. The other main category of guild that has power are

merchants. See, I told you they'd be back. Well, I want to now elaborate on the specifics of merchanthood within the context of the European guild tradition, since you now have the foundational knowledge to understand that nuance a bit better.

As I'm sure you can figure out, instead of crafting items, merchant guilds deal in buying and selling items (and raw materials). They're both the ones transporting the goods and the ones setting up commercial regulations in the market towns where they have a guild charter. Of course, most merchant guilds were associated with only one town, unlike craft guilds. Your city's merchant guild sent its members all around to export your goods and to buy up foreign goods to bring home. However, they only really sold goods to other wholesalers or retailers and not directly to consumers, since consumers generally don't want raw materials.

And in the same way that craft guilds made it illegal to conduct the business of that craft for non-guild members, merchant guilds made it illegal to conduct trade from city to city unless you had a membership. Or at least, the cities they had a charter for. They get rid of competition, control supply and demand, used collective bargaining, shared supplies and warehouses, and shared information (especially about business opportunities with outsiders). Of course, they didn't have the same apprentice > journeymen > master thing going on. It's still often a family business, though, and indeed you find powerful merchant dynasties like the Medicis (who were also into banking). Powerful merchant guilds would necessarily have close relationships with political authorities, since they have a lot to gain from each other. And some really powerful merchant guilds branched out into several different goods, making them more like "general traders."

PCs hired as muscle to protect trade caravans is one of the all-time most popular quest hooks in D&D, and the potential for guilds as employers and factions to gain favor with is obvious. But I'm sure you're at least as interested in the possibility of PCs as guild members themselves. I already briefly touched on merchant gameplay, but what about being members of an artisan guild? Well you can already do that in some games. It's one of the default backgrounds in 5E D&D. And indeed, it's easy enough to just grant players the benefit of at least 1 sympathetic NPC in every town, plus a guild hall to store their stuff. But what about the whole process of training?

Apprenticeship under a master? Maybe, but that sounds a bit boring. Maybe that's what "character creation" represents. Or maybe that's how you incorporate hirelings/henchmen into your game. Each PC has a "proto-PC" in training that they get to upgrade at some point. Journeyman stage? Now that sounds like what an adventurer does. You get some guild money to go out on a journey to your next enterprise, the road filled with dangers. But when you arrive you're back to just doing boring work again for awhile. Maybe the work you do is downtime between sessions, and the adventures that you play out during a session are the things that happen to you on the road in between phases of your training. Create a simple procedure to resolve "how well does your next 3 months of work go?" at the end of each adventure so the PC is set up with some rewards going into the next adventure.

Of course, it can be a bit weird for the whole party to be guild members. I suppose it could make sense for a group of journeymen from different guilds to travel together, if their training happens to line up together. But of course, the most sensible option is to somehow make adventuring itself into a guild...

...Which will be a significant section of Part 3, because I have a good amount to say on how much potential that idea has. Sorry to tease, but this post is already ludicrously long anyway.

Other Neat Stuff

Separate Currencies: I've talked about this before

here and

here but I'll summarize again. Basically, different countries typically use different currencies. Acknowledging this may be useful for those who want to add a pinch of realism to their game, but as in all things I discuss on my blog, it holds my interest because I see gameplay opportunities.

The two versions I've talked about before are 1) separate state moneys, and 2) separate commodities entirely. Separate state money is a bit simpler. Imagine we're playing in a medieval-ish world where each of the major kingdoms uses gold coinage. That means that your money basically has value everywhere you go, but the kings of each country throw a wrench in your plan by putting their own faces on those coins. That means that even though the gold itself will still be desirable, markets won't deal in any gold coins that don't have their king's face on it. The solution? The honorable profession of money changers. Basically, when you enter into a new kingdom or currency zone and you go to the local market, your first stop is at the friendly neighborhood money changer. They assess your foreign coins for their type, wear and tear, and validity, then accept them as deposit, recording its value in local currency. You can then withdraw the money in local currency to conduct trade or, more likely, keep it deposited: the money changer acts as a clearing facility.

My recommendation for the simplest way to gamify this is to just add a small "money change tax" every time the PCs come to a new region. When they go to market, they have to choose how much of their money they want to convert to the local currency, losing 10% of that amount in the exchange because the money changer needs to make a profit. That's it! Just yet another small money sink on the PCs.

As has been often noted, the best way to make money meaningful as a reward is to find ways to make the PCs

need it, which you can achieve by piling up all these minor taxes.

Separate commodities are trickier because the material basis for each coinage/currency isn't shared between the two economies, so they have no value to each other. The example I give is an Overworld that uses silver and an Underworld that uses electrum. Rather than making electrum just part of the normal currency hierarchy but with a weird value, I repurposed it as "exactly equal in value to silver, but only accepted in markets found in the Underdark." Dragons, elves, and undead still deal in it because it's ancient like they are, whereas the mortals of the surface world won't accept it as payment. The gameplay consequence here is that each PC has to maintain multiple economic standings. You can be rich in one country and poor in another, and all your assets are divided. It forces you to travel to markets you might not have otherwise gone to in order to spend your money, resulting in the weird situation where adventurers may voluntarily plunge deeper into the Underworld just to find a market where their electrum treasure will have value.

My own DM used this system in our 5E campaign that just ended. He took it further by having three separate currencies in the campaign: our home country's money, the evil empire's money, and the Feywild money. And boy did we feel the hilarious wealth disparity sometimes. It was funny how, 15+ levels deep into the campaign, we could end up in a situation where one person is completely broke except for in the Feywild, where they inexplicably got rich at some point and they now have to cover the whole party's expenses during the quest spent there.

I would strongly caution against going overboard with this idea. In fact, I had originally urged against doing more than two of these currencies, so I was surprised when my own DM proved that three of them could work as well as it did. But yeah, yet another one of those small things.

Court of Piepowders: Several times now I've used the term "low trust market." This next example is the definition of a mechanism designed from low trust conditions.

In medieval England, during trade fairs, crime rates rose. When dozens and dozens of merchants come in from out of town, the market becomes chaos. Not just thieves, but merchants ripping off customers and each other, too. Hell, even violent crime rose just because of tensions that'll arise from market competition. Because of all this, a temporary micro-court would be set up in the market area with a few schmucks deputised as "justiciars" so that any legal disputes could be resolved quickly. Some might be elected from the locals (with the fun title "Baron of the Piepowders") and others might be foreign merchants who don't have a personal stake in things. This was necessary because the normal arbitration process at the time took a while and required a lot of character testimony from the neighbors of the accused. But most of the people who'd be involved in a crime during a trade fair would be outsiders to the community and who aren't planning on sticking around for long.

So the mayor or bailiff of the town would be there with three or four justiciars. They summoned each party to the dispute, had them make their case, and made their ruling within

at most a day and a half (although often less). As punishment, they could dish out fines or maybe use humiliation, such as holding someone in a

pillory. If someone fails to pay their fine, then their goods were seized, appraised, and sold. If it were a more serious crime, it

should be tried by the royal justices... but the jurisdiction of the piepowders was more solid than you'd think for such an informal, speedy, ad-hoc court. And the name is also great. We aren't sure exactly where it comes from but I love it.

Piepowder courts fall within a broader category historians call Lex Mercatoria, or "Merchant Law." This is the customary body of law that arose to handle market disputes throughout medieval and early modern Europe. Medieval law tended to be extremely localized. Not just the rules themselves, but the means of arbitration. The main method of resolving things was to get together many members of your community who know each party to the conflict and have them all discuss what they think happened. Because that doesn't work for merchants of varying communities and ethnicities, a piecemeal "common law" emerged that was employed throughout the continent, one of the major predecessors to our modern notions of a universal, fair, and objective source of law.

The D&D application here is, of course, to have your PCs be justiciars on a Piepowder Court for a session. Either as an obligation for some title they've been granted or perhaps in exchange for payment from the state, the PCs have to play Judge Judy for a day and hear out the cases of a series of squabbling merchants and make a decision on their fates. Bring in all your favorite NPCs, create moral dilemmas, give the PCs conflicts of interest and bribes, offer them the chance to come up with creative punishments, and make the whole thing goofy as hell.

|

| Although honestly I imagine any group of players who're told they're now a "panel of judges" will take it a different direction... |

Staple Ports: these were designated port cities that had the privilege of exclusive trade for some specific good. For example, the English staple port for wool was the city of Calais (then under English control), meaning that all wool produced across all of England was sent there (collected by agents of the wool merchant's guild paying a low price) and was then either sold to locals to produce into a finished good (e.g. weavers and dyers) or exported to foreign merchants as just raw material (other wool merchants selling it to them at a high price). This would give an advantage to the English merchant guild there, who could monopolize the wool trade and sell it at their own price instead of letting the foreign merchants shop around at the various communities producing wool. It also made the staple port much wealthier, so the choice of which cities you make your staple port is often dictated by politics.

Staple ports are also designated for imports! So if England imports all of its wine, it has a designated staple port for wine. All foreign wine merchants would be required to go to that port first to sell their wares, staying for at least 3 days before they could move on to sell any leftovers elsewhere. Again, pretty big privilege for that town.

Smaller kingdoms like Scotland just had one staple port for all trade, which might make things a lot simpler for someone trying to steal worldbuilding ideas for their RPG stuff. Of course, you can always make it so that PCs can buy goods at any port, but at a heightened cost and risk at the non-staple ports because they're engaging in black market dealing. Either the price is increased from the default for specific goods and you have to roll to see if the PCs get caught, or we assume that most exchanges are black market dealings by default and you instead just advertise a big discount on one or two specific items for each settlement because "this happens to be the staple good of this town." If the PCs suddenly need lots of Iron then the ideal place to get it would be Irontown, and it might be worth making the trip there if they have the luxury, but in a pinch any other town will do.

Tiered Economy: This one isn't actually based on anything real, except maybe

sumptuary laws. It's just a neat gameplay idea that I've seen people come up with again and again (including myself) that's merely inspired by something that already exists in D&D.

So D&D usually has coins in copper, silver, and gold, right? They each have an exchange rate between them, with interchangeable value. Imagine this instead: there are goods that are bought with copper, then there are separate (and probably more luxurious) goods that are bought with silver, and then there are more separate (and finer still) goods that are bought with gold.

And that's it! One of the most simple ideas here. I've seen it brought up before and I've been toying with the idea for years, but I can't think of any time I've ever seen it truly implemented in a finished product.

I would basically envision there being 3 equipment lists in the game, one for each coinage type. And the rules explicitly say "no matter how much copper you have, you can't use it to buy anything on the silver or gold equipment lists" and so on. So acquiring a new coinage type is like unlocking a new tier of play, in a way. Although not so rigidly as something like a leveling system, since you’ll lose and gain varying amounts of each coinage plenty. If you ever spend your last silver, you lose access to the silver market goods and, thus, the silver tier of play. But you can get back in later. XP is rarely this fluid.

Item Availibility by Settlement Size: I've seen tons of ways of doing this before, so I'll just give you the simple method I used:

My game uses a silver standard (sp). There's a master equipment list in the game that's pretty long. There's also 3 size classes of settlement: village, town, and city. Anything worth 100+ sp can't be found in villages, and anything worth 1000+ sp can't be found in towns. Additionally, nearly anything priced at 1000+ takes 1d4 weeks to make/secure, being a hefty purchase. If you examine the equipment list in the book with those limits in mind, I think you'll find that it makes a good amount of sense.

This is usually good enough for most adventuring purposes. But for the players who really get into downtime and want to start playing around with business and economics, I have these additional guidelines:

Each district of a settlement has daily buying and selling caps to represent the limits of how much activity the local economy can handle from one character shopping at market (since sometimes a player engaging in business might find themselves buying and selling items/trade goods in bulk).

The daily selling cap within a poor district is 100 sp, a medium district is 500 sp, and a rich district is 1000 sp. Likewise, the daily buying cap within a poor district is 1000 sp, a medium district is 5000 sp, and a rich district is 10,000 sp. If you need to know the weekly available stock of a generic item in a district (so the player can't just buy an infinite supply of something), it's equal to the daily buying cap of the district ÷ the item's price.

So for example, if you're in a town with 2 medium wealth level districts, and you want to sell a ton of items, you could sell up to 1000 sp worth per day in that settlement (500 sp × 2 districts). Conversely, if you're trying to buy items in that same community, you could buy up to 10,000 sp worth of gear per day from all the vendors in town (although any one type of item is still limited by the weekly supply calculation, so you couldn't just buy 10,000 sp worth of, say, steel helmets). And lastly, if you plan on setting yourself up to be a spice merchant, buying from the town's spicemongers each week and then going abroad to sell it on the road, then here's how you'd determine the amount of spice you could buy in a week: 10,000 sp (daily buying cap of a medium district × 2 districts) ÷ 100 sp (the price of 1 lb. of spices) = 100 lbs. of spice per week.

Gambling: just set up at least one casino somewhere in your game. Let the players waste a session on that nonsense. It's about as novel as the Goblin Market I mentioned last time but it'll be worth it to use just once.

Conclusion