|

| Artist Credit: Wayne Reynolds |

So while you very likely have strong opinions about this word, it might be useful to take a closer look. In this article, I'm going to examine six ways that the word "balance" commonly comes up when discussing RPGs, and why it's important to recognize that they are indeed distinct.

As usual, I will mostly be making reference to ol' D&D as my primary example, but don't mistake that for meaning that this only carries relevance to D&D alone. All kinds of gaming philosophies might benefit from a little bit of thought about these six different meanings for the word "balance," even if there are some that you can safely dismiss. So yeah, balance matters to other crunchy games like GURPS and Lancer and Genesys-system stuff of course, but it can also come up in your rules-lite games, story games, FKR games, lyric games, and so on. If you want to design a Star Wars game and you aren't sure about how to handle the Force, or if you're going to be running a Call and/or Trail of Cthulhu and are crafting a mystery for your investigators, or you're making a random mutation table for a Mothership adventure you're writing, then there's likely something in this post that you should be thinking about. It just might never have occurred to you before because you're only ever thinking of one possible definition out of many.

|

| Artist Credit: Richard Anderson |

This is probably the most widely used and commonly debated use of the word "balance," and yet it's still the one I feel has the most obscurity surrounding it. The basic idea is that, 1) since D&D (and its derivatives) is largely a game of combat-relevant numbers, then you should hypothetically be able to measure the combat power of characters in it, and therefore, 2) you can use those metrics to calculate desired combat configurations.

So uh... what, if any, combat configurations might you desire?

This conversation is almost always reduced to "do you want balanced combat encounters OR ... not." The former side is the norm among the modern and mainstream D&D lineage, where monsters have some kind of "challenge rating" (CR) number included. There's a set of instructions for the DM on how to calculate their fights to be balanced against their PCs at any given level. The latter side is the norm among cranky old-school gamers who claim that the older editions never gave a shit about this sort of thing. That they would just roll the dice to randomly generate their encounters, letting the chips fall where they may.

This is an unnuanced and unhelpful narrative. Both sides are concealing ugly-yet-helpful truths.

Advocates of modern D&D's standard of "balanced" combat have their preference massively undermined by the simple and indisputable fact that the CR system isn't actually that accurate. It would be a lot easier to get on board with if it didn't suck. Most games that attempt something like CR get dodgy results at best. For example, in 5E D&D, by far the number one variable to account for is "number of enemies in the fight." And yet that factor is severely under-weighted in the calculation, throwing everything off.

Advocates of old-school D&D's rejection of balance have two major problems (although the people guilty of each one rarely overlap). The first is the simple lie that older editions allegedly didn't care at all about combat balance. They totally did. Every version of D&D ever published has had some amount of text dedicated to facilitating this goal. It has been there since day 1, and for every grognard who claims to have always ignored it, there are others who have tried in vain to say "bro yeah of course we used it."

The second is the chunk of old-schoolers who actually do have a strong preference for a specific combat configuration. The ones who enjoy "combat as war." Who like the idea of combat being risky and players needing to use their noggins and all that. And yet this second group of old-schoolers often joins the bandwagon of deriding CR and difficulty calculations. This is despite the fact that they also would benefit from those sorts of tools in helping to achieve their desired gameplay results. They join the chorus of voices calling for the abolition of challenge ratings. But by doing so, they work against their own interests. They still ultimately want a calculated difficulty for their ideal combat experience. They just want a different difficulty than the modern mainstream has come to prefer.

And probably the number one thing stalling this conversation from progressing is that:

The word "balance" really should be used to describe the combat-as-war playstyle rather than the combat-as-sport playstyle.

I mean, think about it for a second. "Balance" means that both sides are equal in weight. A "fair fight." But that's clearly not what you're encouraged to set up in a 5E game. If there’s six of you and six of them, and it’s a fair fight, then you know what that means? That for every casualty you inflict on their side, you can expect a casualty on your side. Does that sound like any 5E combat you've ever been in? Of course not. Modern D&D has instead long instructed DMs to calculate combats that are massively one-sided in favor of the players. PC death is rare by design. Meanwhile, OSR "combat as war" advocates are essentially arguing that they want combats that are really, truly "balanced." Then, the fun and challenge comes from the players figuring out how they can unbalance it to be in their favor again.

Once you realize this, it becomes very strange listening to arguments about combat difficulty balance. People are using this word in exactly the opposite way from how they mean it and it's baffling that no one has seemed to notice.

Really, we should throw out the word "balance" entirely and get in the habit of saying "calibration." Almost everyone wants to calibrate their combat encounters somehow, they just want to calibrate it differently and for different ends.

Personally, I'm interested in thinking about qualitative encounter calibration rather than quantitative. Runehammer of Index Card RPG (ICRPG) fame has talked about "challenge tuning." It is, I think, insightful and accessible for even the laziest of old-school referees. To summarize, break an encounter down into three dials that you can adjust as needed: damage, disruption, and duration. When designing an encounter, you increase difficulty by either 1) creating new sources of enhanced damage, 2) introducing environmental effects that harass players, and 3) inducing time pressures that force the players to rush. Books like the 5E DMG rarely acknowledge this kind of thing beyond "contextual factors that might slightly adjust the CR if you feel it's appropriate." That's a shame, because it obscures the underlying sources of excitement in combat. It's pretty fun to brainstorm ideas for encounters for each "dial setting" possible. Try coming up with something that's low in damage yet high in disruption and duration pressures. Suddenly the idea of "combat balance" becomes much more alluring than the math-focused idea of it you used to have.

|

| Artist Credit: Omar Rayyan |

Related to the above, but still meaningfully distinct, is the question of calibrating difficulty across many challenges.

One thing that 3E D&D did change regarding balance is the fixation on individual combat encounters. That the curated, ideal experience to be had at the table is found within but one single battle. And it's easy to be snobby and laugh at this. But while another DM might stress themselves out over trying to perfect that one combat encounter, I occasionally find myself getting stressed about a series of combat encounters. Because lemme tell ya, I may have never beat myself up over making a fight that was too hard (fuck them players, let 'em work for their wins), but I've definitely regretted making a dungeon that was too hard. No fight happens in a vacuum. Blurring the lines between "encounters" creates a lot of possibilities when crafting challenge. But it also creates new complications, as well.

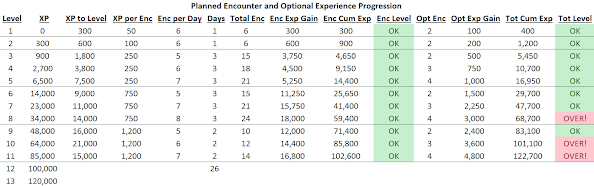

The most familiar way we discuss this type of "balance" is by discussing the adventuring day concept prominent in D&D 5E. I've talked about this at length before but I'll briefly recap. 5E is largely designed as a resource management game where the main resource in question is HP, but you have enough HP to last roughly 6-8 combat encounters before needing to recharge. There's a bit more to it than that, with 50% of your total HP supply existing in a sort of "reserve" that you can only tap into by taking 1-hour short rests throughout the day. Lots of miscellaneous character abilities are limited too, but the point is that a character has a certain amount of "juice" to spend. There is no way to calculate exactly how strong a player character objectively is. There's only "how strong the character is at this moment." A combat encounter's CR should, hypothetically, increase as the PCs' resources decrease. No matter how hard of a fight you think you've concocted for your players, if you throw it to them right at the beginning of the resource cycle then they'll fucking annihilate it. Therefore, the true source of difficulty in 5E instead comes from the aggregate toll of fighting 6-8 combats in a row.

And you can do a lot with this! Fine-tuning the difficulty of individual encounters is tricky. But that's mostly just because DMs are usually trying to thread a very fine needle. They aim for, "guaranteed PC victory, yet still taxing and thrilling." If you instead opt for "comfortable" difficulty combats and then just multiply that by about 6-8, then you have a much more reliable challenge. Ever read the Angry GM? He once had a series of blog posts cataloguing his efforts to make a megadungeon for 5E, and he went absolutely batshit with over-engineering the sequence of encounters seeding each adventuring day. Go ahead and give these charts a skim!

For example, let's look at 1974 OD&D and its close relatives. When the game focused on megadungeons, there was a design standard of "the lower level of the dungeon, the more powerful the monsters." Of course, there's more treasure the lower you get, too. This encourages a core gameplay loop of PCs delving into the dungeon each day and working their way down, level by level, until they've reached the maximum difficulty they think they can handle. There's a nice risk-and-reward incentive system at play. But more importantly I think is to consider the journey that the players have to take as they work their way downward. They have to decide for themselves what they think is a "hard combat." And it always happens in the context of "after fighting through a long series of easier combats" to get there. So there is a relevant place in this conversation for the word "balance" both when talking about 1) making the risks proportional to the rewards, and 2) the pacing of risk distribution in the environment and player decisions regarding them. The players are supposed to be able to gain an understanding of the underlying "logic" of the dungeon's challenges so they can make informed decisions and pick-and-choose individual battles. But this requires a balance of elements that they can pick up on.

A "balanced" adventuring day can also include non-combat challenges, too. My own personal philosophy on running traps in a dungeoncrawl is built on this type of "balance." Again, this is something I've talked about a lot before, but I can recap. While I respect and often enjoy the tradition of big, obvious, elaborate "room traps" that serve as a life-or-death puzzle to solve, I myself really like the alternative option of having many, minor traps that are all very similar and which establish a pattern over time. Most traps are a small HP tax, but if the players never pick up on the pattern then they'll eventually get killed by these recurring HP taxes. They are rewarded for paying attention and using previous knowledge. Yet once again, the design ideal falls apart if improperly balanced. You need at least 3 of these traps for a pattern to form, but too many of them becomes overwhelming. They need to conform to a pattern so that an observant player can have a chance to find them, but they have to iterate somehow so there's still some challenge with each one.

The old-school tradition also likes resource management, obviously. But instead of HP being the primary resource of concern, they focus on light supply, ammo, and rations. But expecting the players to be able to make strategic choices with these things in mind also requires that you, the referee, pay attention to the sources of strain on these resources. Rations don't mean much if all the adventures and dungeons and monster lairs in your game are within a day's walk of each other. But if each one takes several days' of travel to reach, then players have a reason to track how much food they're packing and consuming. Light supply doesn't mean much if you aren't keeping track of time or if the amount of time that passes doesn't meaningfully drain those resources. So you measure the dungeoncrawl in turns. You make it physically large in area. You make sure the PCs' light sources are cheap (e.g. candles, not oil lanterns). And then you see players thinking hard about how deep they care to dwell.

Maybe the best word to replace this type of balance is simply "pacing." I think that's the common thread here. It's just important to note that, in a challenge-based game like D&D, pacing is just as relevant to difficulty as it is to dramatic flow.

|

| Artist Credit: Bobby Chiu |

This is a type that is almost entirely unrelated to the previous two. In games where players get to customize their characters, the choices they are offered can either be "balanced" or "unbalanced." If sub-class A is objectively better than sub-class B, or if X spells are more frequently useful than Y spells, or if one fighting style has lots of synergies that others don't, then you might describe these as unbalanced.

This is a challenge more for the game designer than the DM. But savvy DMs treat game design as an ongoing responsibility! The greatest risk in unbalanced customization choices is that some potentially cool possibilities will get ignored for being under-powered while the over-powered choice gets oversaturated and boring. Assassins should be a fucking awesome archetype for Rogues, right? But because they suck mechanically, no one plays as them (except me).

Of course, this assumes that your players even factor "power" into their customization. Lots of people will gladly choose suboptimal options for a variety of reasons. Not least of which is just "because this one's cool"! It's commonly accepted that the Wild Mage archetype is weaker than the Draconic Bloodline archetype when it comes to Sorcerers. But the Wild Mage is incredibly popular anyway. Why? Because it's fucking hilarious and awesome, duh.

So yeah, if you're the type of player who feels constrained when faced by an unbalanced array of options, "forced" to choose the best ones so you don't underperform even though you think other possibilities are more appealing, then... there's an extent to which that's kind of a "you" problem. But even I will admit that it's possible for this type of imbalance to be a major issue if it goes too far. If one of the options in front of you really is just fucking terrible, then who would be satisfied with that in their game? What value is there in having options that are simply less effective?

Maybe it's kind of like the "Deprived" class in Dark Souls. Why would you choose to be a naked hobo instead of a Knight or Pyromancer? Because you want to be more challenged! But does that same sort of thing apply to TTRPGs? Can unbalanced customization options offer the same choice?

Well... I kinda doubt it. The ways in which a customization option can be "weak" in a TTRPG are not the sorts of things that can be compensated for with sufficient player skill, as in Dark Souls. If the numbers are bad, then the numbers are simply bad. If your class benefits are highly situational and rarely relevant, then you're functionally indistinguishable from a character without those assets at all.

The convenient thing is that you don't actually ever have to compare these different options, so it probably doesn't matter.

For example, let's say I'm making a new character. I'm torn between being a Battlemaster Fighter and a Samurai Fighter. But eventually I choose Samurai. Then what? Well, then I play the damn campaign as my Samurai and I never have to think about it again. There's no Battlemaster near me to compare myself against, so I honestly can't easily tell if I made the "right" choice between those two options. Ideally, I'll probably be with this character for the next couple years, so I won't even be thinking about the Battlemaster again for awhile. Who cares? At least in practice, I don't think this type of balance should really matter to a player who's pretty engaged in the game.

Let's contrast that with its close cousin.

|

| Artist Credit: Beast Pop |

There is a similar yet subtly different form of imbalance. It's the imbalance between customization options that will be chosen by different group members. So rather than one player being torn between sub-class A and sub-class B, we now examine two players who are feeling the imbalance between two entirely separate classes. Now that I've chosen to be a fighter instead of a wizard, I do have a wizard nearby. Their presence will remind me again and again throughout the campaign that I made a less effective decision. Wizards are better than sorcerers, ranged weapons are better than melee weapons, and spellcasters are better than martials. These are all known.

I've heard some people claim that this is the only balance that truly matters, and I can see why. Everyone wants to feel like they're contributing. It sucks if you can clearly see that everyone else is contributing way more than you are. Sometimes it's because you have overlapping contributions and they're just better at it. Maybe two players both want to be the talker for the group and yet one is always doing the talking. Sometimes it's because you have different contributions, but one is just more relevant. Maybe one person wants to play the talker but then you spend the whole campaign in a megadungeon with no NPCs to talk to.

I think most people will agree that it's okay for different PCs to be unequally useful. Just so long as nobody's useless, right? But there's a tricky tradeoff here. The option most likely to achieve "balance" is the jack-of-all-trades. But RPGs are typically about teamwork between a group of friends. And if everyone is equally versatile and effective at all things, then nobody is needed. Specialization leads to its own sort of satisfaction where, say, a situation arises that's seemingly meant for you and you alone.

But we can also attack the notion of "contributing" anything to an RPG experience. That kind of assumes a goal-focused playstyle, right? If you're playing a game where the point is to simply tell a good story, then can there be balance or imbalance between group members? I suppose it would be considered desirable for everyone to get equal time in the spotlight. But the way that people describe this playstyle (on paper) sounds like it should be as easy as totally freeform "playing imagination." Why should such a thespian-minded playstyle need rules or mechanics? I have a feeling that it's because most gamers aren't equipped to just "act" their way through a whole session. They need the support of some character features, toys, constraints, etc. that can help to sculpt the experience a bit for them. So yeah, balance still seems relevant to me, just not in terms of "overpowered" or "underpowered." It might be more along the lines of "over-dictating the narrative / being too strict" vs "under-stimulating creativity / being too vague."

And even in goal-focused games, you have to ask: what is it that characters contribute? In D&D 4E it became codified that all classes must be competent warriors. Because the primary activity you'll be doing 85% or more of the time is combat, it is essential that all classes are good at combat (albeit in their own distinct ways). But in Old-School D&D it was simply understood and accepted that only fighters were competent warriors, and everyone else sucked at combat. This wouldn't be considered "unbalanced" because, to compensate for being shitty at combat, those other classes were good at other activities. This is why it pains me to see the shift in 5E's design philosophy over time gradually move from the Old School outlook (social, exploration, and utility-focused builds are great! Try one out!) to the New School outlook (all new subclasses and feats need to consist exclusively of combat abilities or else they suck and won't make the cut in the next book release!). This has been actively encouraged by the player base, and as a result, most of the content bloat over 5E's lifetime has pushed out non-combat gameplay. Even the newest solution to the broken Ranger class (found in Tasha's Cauldron of Everything) replaces all of the Ranger's wilderness-expertise stuff with more combat abilities instead. Everyone agreed that Rangers needed to be buffed, but we have to also agree on what kind of buffing we want to see.

Party balance is trickier to achieve than it appears. But that's okay. There are some players who would prefer a weaker and simpler character to play as! One of the most common "strengths" one option can enjoy over another is versatility, but versatility is a strength that always carries with it the weakness of being more complex. Everyone knows that the Champion Fighter is one of the weakest subclasses in the game, but it's also the most popular and widely played. The people choosing it definitely aren't doing so because they think it's awesome or entertaining like the Wild Mage Sorcerer or the Assassin Rogue, as mentioned before. The only reason anyone chooses this class is because it's just easy to play. I think that's a perfectly justifiable reason to intentionally include some imbalance in player options. Back in 3E D&D, they even created the Sorcerer class specifically for this reason. It's intentionally a weaker version of the Wizard, but they felt it belonged in the game because it was more accessible than the Wizard.

Another approach that seems outdated is seeking to balance around character potential. In TSR-era D&D, many customization options appeared explicitly imbalanced. What they need is the context of time. Elves, dwarves, and halflings were all mechanically identical to the human Fighting-Men characters of the party but with the addition of a bunch of species-based powers. Doesn't that simply make them better? Well at first, sure. But they have a low level cap, whereas humans can just keep leveling and leveling and leveling. Likewise, Magic-Users were frail weaklings at low levels, but it was balanced out by the godlike powers they'd achieve at high levels. This was seen as an acceptable form of "balance." If you think it's bullshit that your Thief sucks at high level compared to the Magic-User, just remember that the Magic-User had to endure many, many sessions of sucking much worse in order to get where they are now. Some of those editions even had different XP charts for each class, meaning that the pacing of leveling up was an element balanced against the strength of your class.

And another weird idea they used to play with is rewarding more power to characters who are also constrained in their behavior. Paladins are objectively better than nearly any other class, but they face the cost of upholding their moral code. Clerics would be better than Fighting-Men since they're functionally the same thing + spellcasting. But because they're only allowed to wield blunt weapons, they'll never benefit from all those +1, +2, and +3 magic swords showing up from random treasure tables. Which, yes, were intentionally always filled with weapons that Clerics couldn't use.

I think we should continue to explore the potential benefits of this Old-School "balance" in game design, even if it would be rejected outright by the modern mainstream gaming audience.

Oh, and if you're interested in more alternative vocabulary so we can purge the word "balance" from another spot on the list, we can call this one party composition and/or viability. Maybe. In some of these contexts I list. It's hard.

|

| Artist Credit: Andrew Robinson |

Simply put, if the players keep employing the same strategies in response to everything you throw at them, then the game becomes stale. Therefore, a savvy GM should seek to craft situations in which the players are challenged in a variety of ways. Or at least in ways that undermine their core strategies now and then. If doing X is always more effective than doing Y, then people will only ever do Y just for the sake of novelty or, I don't know, some contrarian urge to resist doing the "normie" thing. Something that I think is often left out of the conversation about why modern D&D is so much more combat focused is that it's just more effective than it used to be. Sure, the incentive system is structured around it now and most of your customization features only concern themselves with combat. But even if those weren't true then I still think modern D&D would be combat-obsessed. Why bother outsmarting the opponent if stabbing them will do the trick faster, cheaper, and easier? Then again, I also think the Old-School tendency to increase danger can sometimes go too far. Wanting to incentivize players to use brains over brawn is one thing. But they often make the mistake of making combat totally unviable instead. That sucks if you're playing as a Fighter with a magical talking sword, y'know?

The example I always think of is players peeking through a door keyhole. It's a good idea that a cautious player will always ask to do at every door in the dungeon. But any time a player has found a perfect strategy with no cost and is using it all the time, maybe the GM should throw a wrench in there. Not to undermine the player for having a good idea or anything. Just to keep them on their toes. Maybe if you're nice, you just start including doors with no keyholes. Maybe if you're a little more cruel, you have a goblin waiting on the other side of the keyhole with a needle at the ready.

Where this type of balance comes from will vary. The GM might shoulder some of the responsibility, but it can also be implemented in the game's design itself. For example, D&D (and many combat-centric games) have this recurring issue where players find themselves always just choosing to do a "basic attack" on their turn. It's a very monotonous way to get through a fight scene, and it clashes with everyone's hopes for a more exciting, creative, stunt-orientated choreography. But they choose to do basic attacks because... it's just more effective than doing a maneuver. Sure, you can disarm your opponent in D&D... but they'll just pick up their weapon on their turn anyway. You might as well just deal some more damage to them, right?

So as a game designer, you have an opportunity to think about how you can mechanically balance the different decisions a player could make. Dark Souls has the triad of "block, parry, dodge" as its cornerstone combat maneuvers, which I've seen frequently mimicked in RPGs (such as the recent Block, Dodge, Parry expansion for Cairn!). But this is surprisingly tricky. Continuing with this example, there was a lot of praise for that hot new houserule about the "damage or maneuver" choice offered to the target. I don't actually think it's very good. Stop and think about it: if you want to perform a cool maneuver against your target, then they always have the option to just ignore it and take damage instead. If you're in a situation where doing damage would be more effective than any maneuver, then you obviously won't use this rule. You'll just do an attack, not offering your opponent the option of suffering a manuever instead. And if there's a situation where a manuever would be better than damage, then you have to offer your target the chance to tank the damage instead, which a smart opponent will always choose. Meaning that this system strongly resists manuevers ever actually happening. It practically guarantees that people will only ever be doing damage attacks, even if they want to do something more creative. For all the hype this rule got for being elegant and clever, it was evident to me that few people really considered how it would end up working in practice.

[And that's just the basic application of it. Don't get me started complaining about this dumb rule. It's so easy to think of trickier situations where it just breaks entirely. It's a perfect example of a Dissociated Mechanic that encourages meta-game thinking, exploiting possibilities that exist because of the rules and which don't have any analogy in the fictional situation those rules are meant to represent. But, uh, I digress.]

This type of balance is particularly fiddly because players come up with lots of creative strategies all the time. But if they sneak their way past everything then maybe they should be facing tighter security and detection systems. If they're using illusion magic to undermine all obstacles, maybe they need to face some blind Underdark enemies. In Luka Rejec's Ultraviolet Grasslands, he dedicates text to specifically address the problem of "milk runs." In a game about players operating a merchant caravan, a "milk run" is when the players find a particular trade route that they can keep exploiting again and again and again for safe, endless profit. X town always needs A supply from Y town, which always needs B supply from X town, and gosh darnit these players have a magic item making them immune to the mind-control worms inhabitating the road between the two, so why not just do this forever? Of course, Luka is kinder than me. He advises you to validate this and tell the players, "great! How about you guys pay a hireling to keep running this milk run for you in perpetuity so you can earn passive income? Now let's go explore something new!" And sure, good-faith players who are at the table because they want to have adventures will probably gladly accept that offer. But this is a type of balance where I find the stick to be a lot more reliable than the carrot.

The best alternative word I have for this type of balance is unsolvability.

|

| Artist Credit: Steven Silver |

Most RPGs are "about" something. Call of Cthulhu is about investigating mysteries. Blades in the Dark is about pulling capers. Crash Pandas is about street racing. This is perfectly fine, but I've never met a player who was satisfied in a campaign where they only found themselves doing one kind of thing. Players (and, let's face it, GMs) almost always desire a balance of gameplay styles and activities.

Sometimes this is a balance you have to think about on the macro scale. When my group plays D&D, we have a good mix of adventure types. A campaign features dungeons, wilderness exploration, urban intrigue, politics, combat, investigating mysteries, doin' crimes, downtime, warfare, you name it. Any session where we did something just plain "different" is a session that has a 100% guarantee of praise from my players, at least on that account. Departing from the routine and having the players fight in an arena or participate in a festival or conduct a trial or go on a barcrawl is one of the most reliable ways to create memorable experiences at the table. But I'll admit, I suspect that my group is pretty dedicated to "maximizing" this type of balance.

Most groups don't need that much variety. My brother has been running a Lancer campaign for the last few months, which mostly consists of having a big mecha battle each session. That is definitely more than 50% of their sessions. But it isn't just fights to the death with outer space robots and aliens and whatnot. Sometimes the players are in their mecha and they're playing a weird sci-fi sport for an audience. One time they had a mission to deliver pizza in their mecha. He ran the Mothership adventure "Hideo's World" in that campaign, where the players had to enter a video game filled with bugs, glitches, and ads. These adventures still "fit" with the campaign, but they're refreshing.

And even if you're committed to one sort of activity in your campaign, you still need a balance of elements in it. A lot of you are probably just running dungeoncrawler games, especially the nerds who love themselves a big ol' megadungeon-centered campaign. But I bet you know better than to just fill every chamber with orcs, right? Arnold K's famous dungeon checklist post is, fundamentally, a post about game balance.

Of all the types of "balance" in this list, this one might seem like the most "well, duh." Everyone knows that you gotta have variety. But I do see this one ignored weirdly often. Hexcrawls are a famous example of a solid and potent gameplay convention that is really, really easy to do poorly. It's very common for an ambitious hexcrawl campaign to end up bogged down in an entirely bookkeeping-focused procedure. Where players aren't really making interesting choices so much as just, like, suffering penalties from weather, rolling not to get lost, consuming rations, calculating travel times, and having meaningless random encounters to pad out the session.

I feel like the tradition of adventures constructed from random tables does a lot to directly undermine this type of balance. It depends on how robust the tables are, of course. But procedurally-generated scenarios are the most prone to being a bit bland and repetitive. They are literally formulaic. I find random tables to be a great starting point for getting some pieces on the table, but the results need to be developed on with a bit more imagination before the scenario is play-ready.

|

| Artist Credit: Emily Warren |

"Balance" has been reduced to a near-meaningless buzzword used only in service to specific agendas. It's casually tossed around in highly-opinionated arguments about gaming in both positive and negative fashion. It's either a shorthand for "good and desirable" or "bad and undesirable." This kind of cheapening of words isn't usually that big of a deal. You can butcher our language and it'll be fine. It doesn't really matter if you're careless in saying "jealousy" instead of "envy" or if you say "the people were evacuated" instead of "the building was evacuated." But "balance" is a technical term in game design. Nuance in its usage is more valuable than in everyday speech. And as this word gets rendered totally meaningless, I stand here on the sidelines watching communication completely and utterly breaking down in real time. People totally talking past each other because of this one magic word.

I've spent a good chunk of this post emphasizing the need to distinguish between these concepts that are too often conflated. I've offered a few alternative words we can use to make a more nuanced vocabulary. But I do think that there is ultimately a common thread to all these things we call "balance."

At the heart of it, all of these concepts are seeking to ensure that your gaming experience stays thrilling. Different people will find different parts of the experience to be their preferred source of thrill, whether it's sport-like combat, tipping obstacles in their own favor, managing resources, making a build with lots of neat toys, everyone at the table having their time in the spotlight, challenges that force creativity, or just something fresh and novel.

I know many people will instinctively recoil at being asked to give consideration to these ingredients of their gaming experience, because it feels like I'm asking them to solve the game. "If the game isn't balanced properly, then you won't have fun!" Of course that's a load of shit. Everyone eventually gets tired of calculating CR values and decides to just eyeball it one day. And every time, they discover on their own that they'll still have fun even if they don't try to balance things at all. So clearly this is a silly thing to care about.

But that's probably just because RPGs are generally fun. If everyone's just acting pretty reasonably, they'll probably make it mostly work fine. It's the instances of extreme imbalance where you get a reality check. Suddenly the game stops being thrilling for everyone and that's a problem. Maybe combat went poorly, resource management turned into meaningless bookkeeping, someone feels like they made a bland or shitty character, somebody is left in the dust while everyone else has fun, the players cheese their way through every challenge by abusing an exploit, or they just get tired of doing the same thing all the time. An attentive GM who notices these issues will find that the answer is to re-balance something going on in the equation.

As a designer of games, adventures, encounters, or whatever else, you're perfectly fine settling for "good enough." Yes, I'm beating up on imbalance in D&D 5E, but the truth is that none of the classes are that weak. It's all relative. People still enjoy playing Rangers and Monks. You don't need to fine-tune the experience. But I think that one of the reasons why, for example, my own combat encounters go really well when I merely eyeball them is that I still do understand all the CR calculations that I could be doing. A really thorough understanding of balance goes a long way towards informing a more hands-off "just eyeball it" approach to things. And when I'm designing classes for my fantasy heartbreaker RPG, I don't stress myself out over making sure things are balanced. But I do take a look around at other features I've written to give myself a sense of the numbers I've been working with so far when I'm designing a new feature.

I wrote this post by spending a long time jotting down every way that I saw people using the word "balance" in the RPG parts of the internet that I spend time in. There were six different meanings that came up again and again. But I bet there are more.

-Dwiz

[P.S. If you enjoyed the images throughout this post, see here for their origin story. Fun little piece of D&D's lost online history.]

I would love to see you elaborate on your hex crawl section. You mention that random tables make a good starting point but they require a little TLC. Do you have any good examples or previous posts that might be worth reading on the subject?

ReplyDeleteYeah, I'd be happy to. For further reading, I'd like to recommend Prismatic Wasteland's recent series about hexcrawling, where he covered random encounter tables at the beginning of part 2 (https://www.prismaticwasteland.com/blog/hexcrawl-checklist-part-two). This also includes even MORE reading links for you, if you'd like.

DeleteBut my short take is that the most common way that random encounter tables get designed, and one of the worst ways, is that they'll just have a bland set of monsters or wildlife that just "appear" before the PCs, and then... a fun encounter is expected to follow from there. Maybe one side is ambushing the other, but even an encounter that's just, "and then you get attacked by a squad of bandits, go kill 'em" doesn't have much going for it. They're often lacking in motives, an activity they're currently engaged in, a role within the context of the greater area that they're wandering in, and basically just anything that could elevate them to more than mere combat filler. I have had the misfortune of both playing in AND running a few too many hexcrawls where the main "adventure activity" that broke up the logistical gameplay was pretty much just, "alright, you get attacked by wolves. Fight some wildlife now."

Showing up very late to the party, but whenever people talk about random tables and how they can suck (your description is spot on, by the way; I see those constantly), I always think of Final Fantasy: Crystal Chronicles, for GameCube. Did anyone here play that?

DeleteOccasionally, while you were traveling on the overworld map with your little caravan, you would trigger their version of random encounters -- except instead of fights, they could be one-off meetings with named NPCs that would show up again later, or quick conversations where you were given agency in a dialogue box only once to make an impression on someone, or rumblings of things that might happen later, or, or, etc.

They were great for worldbuilding, flavor, and for instilling a sort of "Will this choice I made here come back later, in some fashion?" mystique, that kept you guessing as a player as to what the game was choosing to remember and when. I encourage all DMs/GMs to make their random encounters more like that -- quick portraits of the world, conversations with passing merchants where you get to learn something or impress someone, a gambling match where you win a cool, but unmagical trinket that might come up again later. And if you ARE going to make it combat, make it a quick scrap with a tiny story to tell.

But yeah, all D&D sourcebooks have them looking like "1. A scorpion. 2. A big scorpion. 3. I dunno, a weird plant. 4. A scorpion plant."

"One thing that 3E D&D did change regarding balance is the fixation on individual combat encounters." This is undeniably true with regards to the effect 3e had, which is why I think it's interesting that the 3.0 DMG's advice on CR was that about 50% of encounters should be equal to party's EL, some should be slightly higher, some slightly lower, and a small number very easy or very difficult. They had the old school encounter variance baked in as a principle, but it got lost somewhere.

ReplyDeleteRE: the damage-or-maneuver mechanic, it seems to me that it only works if that's just how every attack roll functions. Assuming two parties at full health, the start of the battle will be basic attacks all around and then descend into mostly maneuvers as people get low on HP. Over the course a session the players would probably take a lot of maneuvers to not die, which could showcase lots of fun monster abilities if the DM was prepared for it. I'm still not convinced that that's *good* though.

Encounter variance is at least _suggested_ on page 84 of the 5E DMG, but I think the failure mode is this:

Delete- more detailed combats from 3E/4E/5E are slower

- at-EL or below-EL combats are less challenging

- slow combats without much risk are unrewarding

... so there's a gradient towards fewer tougher fights. 6-8 equal-CR fights in 5e will take a lot of table time, not provide a lot of excitement, and so be perceived as boring. Cue our host's mention of pacing.

A good and interesting read. One small bit of meta feedback: I've followed your blog for about a year now, but I find I get intimidated out of reading your longer posts more often than not. I feel like this article (and several others) could have been posted as a series of shorter posts, and this would have made me more likely to read and digest them.

ReplyDelete