This post collects a lot of miscellaneous observations and advice, some from other thinkers and some from myself. It's all basic-level. There's plenty of stuff out there far more advanced than this. This is not written with any particular game system in mind, and it includes a mix of game master advice and game designer advice.

Here's the fundamental problem of this topic: most of the time, preserving the players' agency is paramount. But fear complicates this priority. Fear is an involuntary mental state, but it can shape your behavior in profound ways. No heroic adventurer would choose to be afraid when faced with peril.

Ideally, you trust the players to roleplay their characters' emotions on their own. "If it seems like your character would be afraid of this, then try to play them like they're afraid." And if everyone is participating in good faith, they'll try their best. But unlike other emotions, authentically roleplaying fear is much easier said than done.

There are a number of ways to help resolve this problem. Different games and playstyles offer their own answers. Some of them contradictory, some of them mix well. Here's the stuff that makes sense to me based off of all my experience. I'm splitting this into three sections: 1) Player Fear, 2) Mechanical Fear, and 3) The Overlap.

Player Fear

One approach is to try to just actually scare the players themselves. That's what most people expect out of a horror RPG, after all. And when the player is scared, their character will be, too.

This is a concept in roleplaying known as "bleed." Bleed (coined by Emily Care Boss in 2007) is the phenomenon where a human player's emotions bleed into their fictional character's emotions or vice versa, when a character's emotions bleed into the human playing as them. An example of the former would be when you come to the session kind of annoyed, you didn't get much sleep, work sucked, traffic was bad, etc. and now you're playing your character as having no patience left and being overly suspicious of everyone's intentions. An example of the latter would be when a longtime NPC ally is killed in the game and you, the player, find yourself feeling genuinely sad over it.

Bleed is not intrinsically good or bad. It always depends. For some people, a powerful experience of bleed is the number one thing they're seeking to get out of an RPG. There's nothing more immersive than the moment where the barrier between you and your character completely fades away and you feel like you're really living their life. It sounds pretty cool, right?

On the other hand, bleed can end up being negative, sometimes even harmful. You're probably familiar with the proliferation of safety tools in RPGs. There's a lot of debate about what practices are effective or sensible, but the guiding principle is, of course, consent. Some players want to be scared, others don't. More importantly, one player may be okay with some forms of negative bleed, but not others. A player may be very receptive to having a horrifying experience, but also draw a line on certain specific topics. So yes, feel free to attempt to scare the bejeezus out of them. But don't ever cross those lines.

More than consent, it also requires buy-in. A player may say they have no objection to being afraid, but that isn't enough. They usually have to want it as well. And it takes teamwork, too. Everyone at the table is working together, and if just one person doesn't buy into the agreed tone then they can derail everyone's experience by being too goofy.

So if everyone is on board, then how do you achieve this "fear-bleed" effect?

Surface-Level Spooks

This is the main thing you'll find discussed in most resources talking about fear in RPGs. "The key is atmosphere!" Dim the lights, put on some spooky music, do your best impression of Peter Lorre to sound creepy, etc. I don't put a lot of stock into this stuff, but give it a try. It might work for you and your group.

The one thing in this category I'll give my endorsement is the power of a properly menacing description. The game is a conversation first and foremost, after all. If your players are facing some big horrible gross monster then make sure they know it.

That said, the act of describing a thing requires a light hand. You may be tempted to include lots of complicated details. This is less effective than just giving one or two evocative and memorable elements. Instead of long, grotesque descriptions, highlight just one or two disturbing features. Players tune out during monologues. They can't process too much information all at once.

Scary Stories

All that stuff is kind of superficial. Really what you want is for the situation to be scary. Dim lighting can suggest fear, but the players need an actual reason to be afraid.

Obviously, "how to craft a scary story" is the subject of decades of investigation by authors and screenwriters and everyone in the business of making horror entertainment. There's no single perfect formula to achieve this. But one of my favorite resources (and one which is specifically written for RPG purposes) is a guide called The Trajectory of Fear by Ash Law. I'm going to give you an abbreviated version of it, adapted to some of my own thoughts as well, but I highly recommend reading the original. I don't agree with all of Law's claims but it's very good.

The basic idea is that effective fear follows an arc that progresses over the course of the story. You have to let it escalate, making sure to give the right amount of attention to each step. The four main steps, which are also each a slightly different type of fear, are unease, dread, terror, and horror.

Begin with the normal. You need a horror-free baseline. Some notion of a status quo, time for players to invest in the world, experience some positive emotions. This might sound like a waste of time but it's important because the horror needs to contrast against this part. It's also where you set up the stakes.

Punctuate the first half with elements of unease and dread. Start with just weird stuff. It's okay to be mysterious, as long as you don't draw it out for too long. But also, be intentional with your tension-building elements. They shouldn't just be unsettling for its own sake. They should foreshadow what comes later, so they can also serve as clues for clever players.

The diagram above shows only one peak of terror + horror, but in reality there could be many. A long roller coaster has several big hills. Once you reach those parts of the trajectory, my best advice for you is this next principle:

Suspense Over Shock

The most thrilling moment is right before the consequences are suffered. Don’t hold back on having a monster eat or kidnap a player character when the time comes. But the players can get very worked up just by being told that “the monster is making its way around the corner” or “you hear a scream from the room below and the shatter of glass.” Thus, insert an extra step into your process just to build suspense.

Note: this technique also nerfs the difficulty of the situation a little bit. What's more difficult for the player to overcome?

A) "You know the werewolf is in the building. It suddenly drops down from the ceiling and attacks you." Rolls 1d20+8 to hit.B) "You know the werewolf is in the building. You hear movement above you, and then saliva begins dripping down. You look up and see the werewolf about to drop from the ceiling and attack."

The second one gives the players a chance to do something before that horrible +8 attack roll is made. It's a lot more forgiving. But it counterintuitively feels more threatening, which is what you want. Delay the consequences to build suspense.

Another example is to target NPCs before PCs. As in, if the party has hirelings or NPC escorts or whatever, of if there's some hapless bystander at the moment, then I usually have the monster attack those guys first. Now of course, I'll admit that this is metagaming. If you feel that this violates the sanctity of impartiality, then I totally understand. But understand that I'm not doing this out of mercy. I'm doing it because it's more effective at scaring players. My motivations are entirely sadistic.

If the monster appears and immediately kills a PC, now they're just dead and the tension is over for them. It ended as quickly as it began. But if instead the monster appears and immediately kills an NPC, right in full view of the PCs, then tension is established. You're showing them what's at stake.

Lastly, on the topic of player fear:

Calibrate Your Expectations

You can follow all this advice and still not get the outcome you were hoping for. That doesn't mean you did anything wrong or that the advice was bad. But you may have had unrealistic expectations. Why?

- Not everyone can be scared by fictional media. You might (understandably) make the mistake of thinking that horror fans consume horror media because they want to be scared. But I myself am a huge horror fan, yet horror movies don't scare me. I can count on one hand the number of horror movies that have even creeped me out. That might not sound right, but I'm actually not alone. A lot of us enjoy horror for other reasons. We appreciate it for its craft, its imagination, its mood, its themes, and so on. If I ever happen to be actually scared, I count that as a huge bonus. But I've accepted that it's a rare and special thing, and I don't hang my enjoyment of the genre on that. Likewise, you shouldn't hang the success of your horror game on whether or not your players are afraid.

Here's a quote from the Mothership Warden's Operation Manual by Sean McCoy:Most of the time, your players simply want to have fun in a horror setting. This means they want to play characters who feel afraid, while they the players just sit back eating chips and rolling dice.

- Fear doesn't always look like fear. Okay, let's say for the sake of argument that your players are receptive to fear and they do want to be afraid. Even when that's true, you still might not recognize when your players are afraid. Just because they're laughing doesn't mean they aren't on edge. Again, you might (understandably) make the mistake of thinking that laughter and joking are the opposite of fear, that it's undermining their capacity to feel afraid. But many people have weird stress responses, including laughter. Joking around about the tension does not automatically diffuse it for everyone.

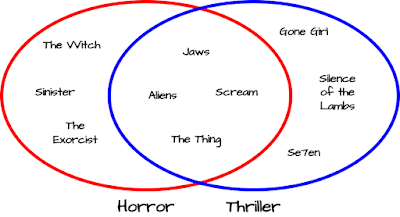

- Fear is part of a wider emotional landscape. Building off of the previous point, let's remind ourselves of the sister genre of horror: the thriller.

You may disagree with how I categorized some of these, and you may also want to point out that there are other genres present in these examples as well (comedy, sci-fi, action, etc.). But the point is that there's overlap. The primary emotion of the thriller is excitement, which often means laughter. Fear is a notoriously difficult emotional response to achieve, but nailing thrill is a very worthy alternative that is already adjacent. Another adjacent emotion is disgust, which I think is likewise a great target for RPGs.

Alright, armed with that knowledge, we can now move onto the second half...

Mechanical fear

One of the most common and straightforward purposes of mechanics is to simulate. We can use a rule or resource to model all kinds of things. Often they'll be tangible elements like movement, damage, perception, etc. But obviously you're no stranger to mechanics that model the intangible, the psychological or social or metaphysical. If you can create rules to govern the simulation of a person's intelligence, their charisma, their morality, or their emotional bonds, then surely you can do the same with fear, right?

Well, that brings us back to the main problem that I stated in the intro. So you tell your players, "try to roleplay your fear accurately." It seems like a simple ask. But this can actually be really hard, for two main reasons.

The first reason is that it's hard to judge when something would be meaningfully scary to your character. "Should my character be scared of searching through these bookshelves in the dark?" "I dunno, does that sound scary to you?" "Yeah but so does getting into a fight with a bunch of guys who have swords." How do you know what your character's fear threshold is?

So how do we reckon with that? I have three solid, reliable tools for this:

The first reason is that it's hard to judge when something would be meaningfully scary to your character. "Should my character be scared of searching through these bookshelves in the dark?" "I dunno, does that sound scary to you?" "Yeah but so does getting into a fight with a bunch of guys who have swords." How do you know what your character's fear threshold is?

The second reason is that it's hard to judge just how much it should affect their behavior. Even if you are sure, "okay, my character should definitely be afraid of this tentacle brain monster. So... does that mean I piss myself now? Or can I reasonably tough it out?" You can justify whatever answer you want.

So how do we reckon with that? I have three solid, reliable tools for this:

Worst Fear

The iconic fear mechanic in an RPG is the "Sanity check" from Call of Cthulhu, which has inspired many similar "freak out" mechanics in other games. Because of these, we often think of the consequence of fear being "doing something you wouldn't have chosen to do voluntarily." That it impairs your decision-making.

But I say that this is actually a fairly extreme consequence of fear, and that we can reasonably relegate it to rare edge cases. Instead, the more common effect of fear is that it impairs your effectiveness at doing things. What's important is that, most of the time, an afraid PC still retains agency.

But I say that this is actually a fairly extreme consequence of fear, and that we can reasonably relegate it to rare edge cases. Instead, the more common effect of fear is that it impairs your effectiveness at doing things. What's important is that, most of the time, an afraid PC still retains agency.

Thus, my foundational fear mechanic is to simulate it with a simple action penalty. In my game, that means rolling dice with a disadvantage. Your game has some equivalent, I'm sure. "You're afraid of the demon clown, so roll your attack at a disadvantage." It's deceptively straightforward. This means the player knows exactly how their fear affects their behavior. It's a simple mechanical expression of character fear that anyone can understand and smoothly integrate.

But we still have the first problem. What triggers a fear penalty? I have a similarly simple answer: assign every player character a worst fear. This is one thing that a player knows for sure would be scary to them. While there may still be questions about other situations, this is one trigger we can be certain of. Seed your scenarios with that worst fear. Then, whenever the PC attempts an action where their worst fear is relevant, apply the penalty.

Does this sound, like, ridiculously simple? Surely it can't be that easy, right? Honestly, it kind of is. This goes a really, really long way. Here's my d6 × d6 table of worst fears for Tricks & Treats.

But we still have the first problem. What triggers a fear penalty? I have a similarly simple answer: assign every player character a worst fear. This is one thing that a player knows for sure would be scary to them. While there may still be questions about other situations, this is one trigger we can be certain of. Seed your scenarios with that worst fear. Then, whenever the PC attempts an action where their worst fear is relevant, apply the penalty.

Does this sound, like, ridiculously simple? Surely it can't be that easy, right? Honestly, it kind of is. This goes a really, really long way. Here's my d6 × d6 table of worst fears for Tricks & Treats.

"Jump Scares"

In Tricks & Treats, I use these for when an NPC pulls a scary trick on you. You could also use them for, like, traps and stuff. It's basically just a saving throw. But the technique itself is a verbal sleight of hand I want to teach you.

Here's how I do a normal dice roll:

Here's how I do a normal dice roll:

- The player declares an action they want to attempt.

- I determine that this would require a dice test, and inform the player. I tell them the difficulty and what the outcome of the roll would represent.

- Negotiation over modifiers and whatnot.

- The player can decide whether or not they want to attempt it. If so, they roll their dice and the things happen.

I like being extremely transparent about dice rolls. I want you to be fully armed with whatever knowledge your character might reasonably have. I want to give them the benefit of the doubt, that they can likely tell the limits of their own abilities pretty accurately.

A "jump scare" is when you break this rule. Which, of course, is only significant if you otherwise are very consistent in following the rule. If the player grows accustomed to the above stated process, if they take that level of transparency for granted, then they'll be shocked and disadvantaged once it's taken away.

The difference is this: normally, a player is probably aware that the action they're declaring would trigger a die roll, and they get the chance to back out. But if they trigger one unknowingly, then they don't get that chance. You simply tell them what to roll. They don't know why, they don't know what's at stake. Don't worry, you'll tell them in a couple seconds and it'll all make sense.

If the player expressed caution (even if it was only vague caution) or they possess some relevant preparedness, you tell them to roll with an advantage. If their worst fear is relevant, you tell them to roll with a disadvantage. In either case, you don't say why. You simply instruct them to make the roll with whatever modifiers you deem fit, no chance for negotiation. Again, you can tell them right afterwards and it'll make sense.

This technique is weirdly effective at jolting the player, and it actually does take away one of the most important assets the player uses throughout the game.

If the player expressed caution (even if it was only vague caution) or they possess some relevant preparedness, you tell them to roll with an advantage. If their worst fear is relevant, you tell them to roll with a disadvantage. In either case, you don't say why. You simply instruct them to make the roll with whatever modifiers you deem fit, no chance for negotiation. Again, you can tell them right afterwards and it'll make sense.

This technique is weirdly effective at jolting the player, and it actually does take away one of the most important assets the player uses throughout the game.

Yes, yes, also Panic

Panic rules are useful for simulating those more extreme expressions of fear. I think that too many horror games over-rely on them, but they can definitely be useful.

I've been critical of Mothership's before, but it has a lot of qualities I liked, and I did use it as one of my references to design my own. I'll share both here, for reference.

I've been critical of Mothership's before, but it has a lot of qualities I liked, and I did use it as one of my references to design my own. I'll share both here, for reference.

From Mothership 1E, and...

...from a lil ghost bustin' game I whipped up titled Who You Gonna Call.

You can see that this one builds off of the Worst Fear tool. Honestly, I would say that any horror game probably only needs one or two solid horror mechanics. Go research some more games and plunder your favorite tools, but don't try to squeeze all of them together into one game.

A good panic system should take awhile to build up. If you're going to steal the player's agency, it's usually better for them to see it coming than for it to be sudden and unexpected. Remember, suspense over shock. But what I didn't care for with the Mothership system is that 1) the trigger is too rare, and 2) the effects tend to be incremental and situational and oftentimes literally negligible.

Thus, I tried to make my results a lot chunkier. Something immediately impactful.* Importantly, they're also a very short term theft of the player's agency. If you're going to violate something so sacred, keep it brief. Literally just one action in one moment. Nobody likes having to sit out for a whole combat because their character is freaking out. But they can usually accept a timeout if it's only for one turn. Trust me, that's usually punishment enough anyway.

Notice also that the stress triggers correspond with unease and dread elements while the panic triggers correspond with terror and horror elements. Thus, the mechanical progression maps onto the narrative escalation pretty naturally. Neat, huh?

Now for the most important part...

The Overlap

When player fear and mechanical fear feed into one another, the total effect is greater than the sum of its parts. What do I mean?

For an example, the "jump scare" technique serves to disadvantage the player in a minor way, yes. But it also tends to startle them. Being forced to make a dice roll that you didn't mean to feels uncomfortable. While the effect isn't huge, it does contribute to the ongoing trajectory of fear. Remember, the roller coaster needs to start with a lot of little hills.

As another example, let's look at the "worst fear" technique. In my experience, players often end up self-policing their behavior to be more restrictive than the rules instruct them to.

GM: "Anyone who wants to try getting a baseball has to snatch it away from the protection of the guard dog."Alice: "I'm scared of dogs, I won't even try it."

And, like, this is kind of irrational, right? All else being equal, the mechanics just say that she would roll her attempt at a disadvantage. Yet there she goes, letting her fear control her. Because fear is often irrational.

This is the real juice that makes player fear worth it. Not simply for its own sake, but for how it then impacts the gameplay. When a player is actually afraid, it impairs their decision-making without the rules forcing them to.

Honestly, there's probably no better example to illustrate this than the original, foundational mechanic in the earliest RPG of all: hit points.

Old-school D&D is often referred to as a "horror game" by its fans. There's all sorts of various ingredients they can point at to support this description. But if we're being honest, it comes down to one thing: you have shit HP.

Players are usually pretty invested in their character's survival, which HP is used for. But when it comes in large, bloated amounts, it feels more like an expendable resource for you to take advantage of. That's the kind of thinking that makes you act like a Greek demigod. In reality, HP is a measure of how many mistakes you can make. The reason you might not normally think of it as such is because modern heroic games like D&D 5E almost never meaningfully test your player character's survival. You can take like 20 hits and be fine. Lots of room for mistakes. But if the mechanics are built such that you'll die after only 1 or 2 hits, then you actually have to face the prospect of your character dying.

Because the mechanic is punishing, that directly translates to the player being more afraid of death than they otherwise would be in a less punishing game. And when the player is afraid of mechanical consequences, they play their character more cautiously to avoid triggering those mechanics. The player's fear of the mechanic is perfectly analogous to their character's fear of the situation. Beautiful.

-Dwiz

*I'll admit that I don't care much for result number 6, and I wouldn't mind replacing or revising result number 4. Game design is hard.

Haven't seen the "Jump Scares" chapter articulated that way before but makes totally sense.

ReplyDeleteAnd in case it wasn't intentional deletion: the linked blog post about Mothership isn't there anymore.